Public debt in Latin America’s major economies is on pace to average 55 percent of gross domestic product this year, up significantly from 34 percent in 2013 (when the region’s commodity boom ended) and reversing the improvements achieved in the earlier part of this century. The regional figure reflects the seven economies that account for about three quarters of economic output: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay.

That level is below the 93 percent global level shown in the October Fiscal Monitor, but it is still high by Latin America’s historical standards and the region’s capacity to borrow. Financing costs average 3.8 percent of GDP, well above the 1.7 percent in advanced economies and the 2.5 percent in other emerging markets. The region is vulnerable to domestic and global shocks, including from commodity prices. And while it has increased much-needed social spending, fiscal policy is not helping to boost productivity and accelerate growth as much as it could.

A recent study included in our October 2024 Regional Economic Outlook shows that the progress in reducing debt that Latin America made at the beginning of the century had essentially reversed in the years preceding the pandemic. During the commodity boom of 2004-13, debt fell from 50 percent to 34 percent of GDP, supported by strong economic growth, government budget surpluses, and appreciating domestic currencies. However, once the boom ended, primary surpluses turned into deficits, currencies weakened, and growth slowed.

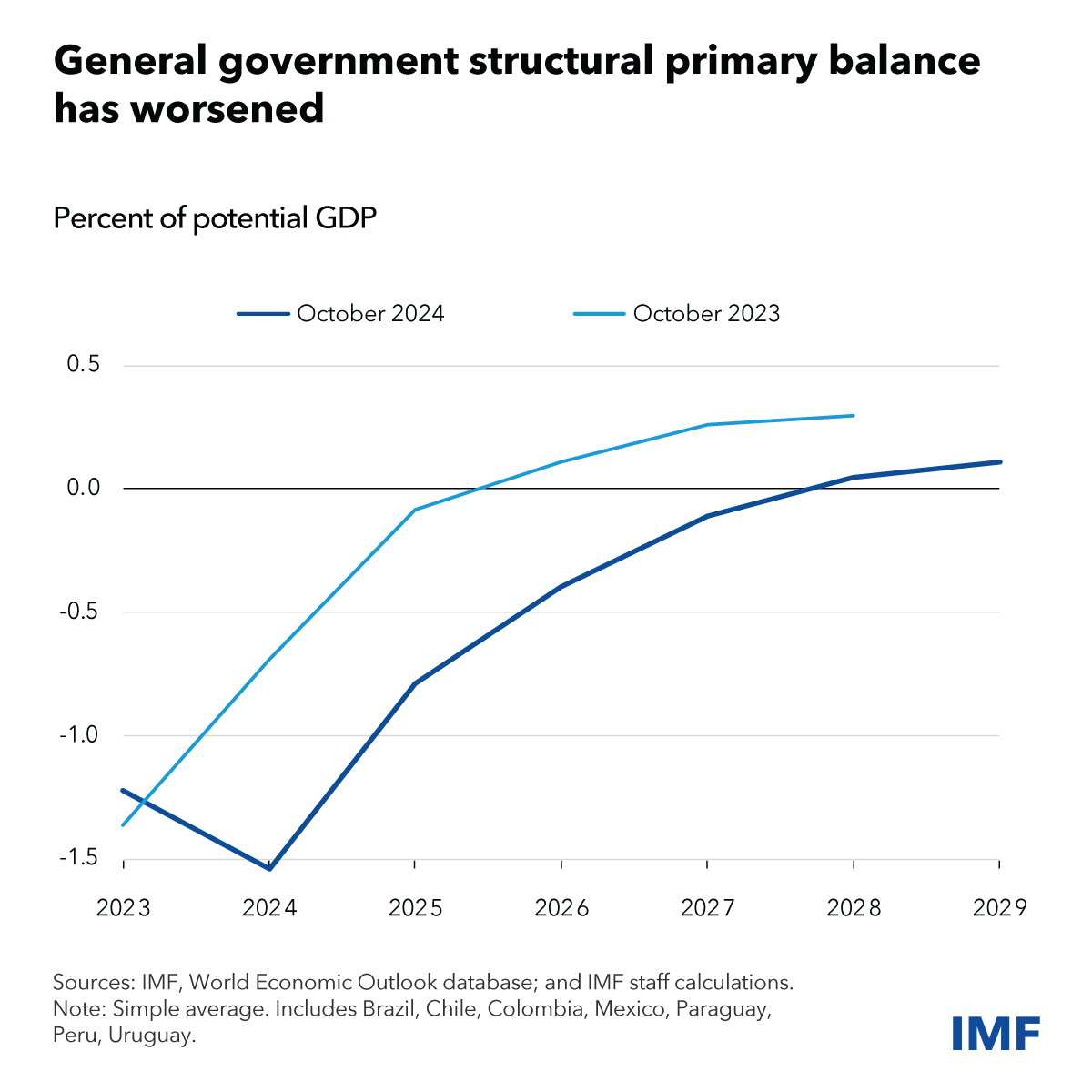

Public finances weakened despite the growing use of fiscal rules. Although countries went a long way in setting targets for spending, and budget balances, such targets were frequently modified and relaxed over time—in effect postponing the necessary adjustment. For example, one year ago, the IMF forecast assumed an average structural primary deficit (meaning excluding interest payments) of 0.1 percent of potential GDP for 2025. That has now widened to 0.8 percent even as economic growth projections in the region are little changed.

Lackluster growth prospects—reflecting low productivity and investment, and shifting demographics—and persistently high financing costs pose important challenges, given the high levels of debt. The study finds that high financing costs largely reflect domestic factors, including low government effectiveness, an unfavorable history of stress and defaults, and lower foreign exchange reserves. The combination of low growth and high interest rates means higher debt burdens in coming years for Latin America.

During the pandemic, public debt jumped globally for good reason—emergency spending helped protect the most vulnerable and avoid an even worse collapse in economic activity. While still higher than before the lockdowns, debt has declined since 2022 as economies recovered and crisis support was withdrawn.

To stabilize debt, the seven largest countries in the region have announced ambitious fiscal consolidation plans, aiming to revert an average deficit of 0.8 percent of GDP in 2024 to a surplus of around 0.6 percent by 2029. However, these plans have suffered delays, and lack political support. In many countries, they rely on raising additional revenue and spending cuts that have yet to be identified.

Stabilizing debt is an important first step, but not enough. Truly reducing debt over the next five years is necessary for countries to rebuild their capacity to address future shocks, as it happened during the pandemic.

Debt Rise

As documented in the study, turmoil in global financial markets could affect economic growth, raise debt financing costs, and weaken exchange rates. If this happened, debt could increase by about 8.5 percentage points of GDP by 2029, compared to current projections. Similarly, the study documents that a commodity price shock or a natural disaster could increase public debt by about 6 to 9 percentage points of GDP, respectively, over that horizon.

The deterioration of public finances and the increase in debt after the end of the commodity price boom in 2013 suggests that existing fiscal frameworks were not strong enough. Effective fiscal frameworks can guide policy choices and offer the resilience and flexibility to deal with unpredictable events. Some countries are strengthening them through the recent introduction of public debt targets, such as Paraguay, Chile, and Colombia.

However, in trying to address the problem, some have become overly complex at the expense of transparency and accountability. There are several areas for improvement, including providing more resources to independent fiscal institutions and strengthening accountability mechanisms. And it is critical to avoid reforms that imperil public finances.

With lackluster growth prospects, high financing costs, and an uncertain world, now is the moment to reduce deficits and enhance fiscal frameworks, both of which help with reducing borrowing costs. It is urgent for countries to rebuild the space used in the last five years. Fiscal discipline will also help tame inflation, as our October report notes, which would ease the pressure on monetary policy.