So far so good. These words are probably a fair assessment of Europe’s progress thus far in its struggle against inflation. Policy interest rates have been raised resolutely, central banks have signaled commitment to keeping them high for as long as necessary, and inflation is down sharply from the double-digit highs of last year.

Underlying inflation, however, is proving more stubborn than headline inflation, which includes energy, food, and other more volatile items. Bringing it back to target, durably, remains a matter of urgency. Entrenched high inflation is distortionary. Moreover, prolonged inflation means prolonged high real interest rates, which would hurt private and public investment and therefore future growth.

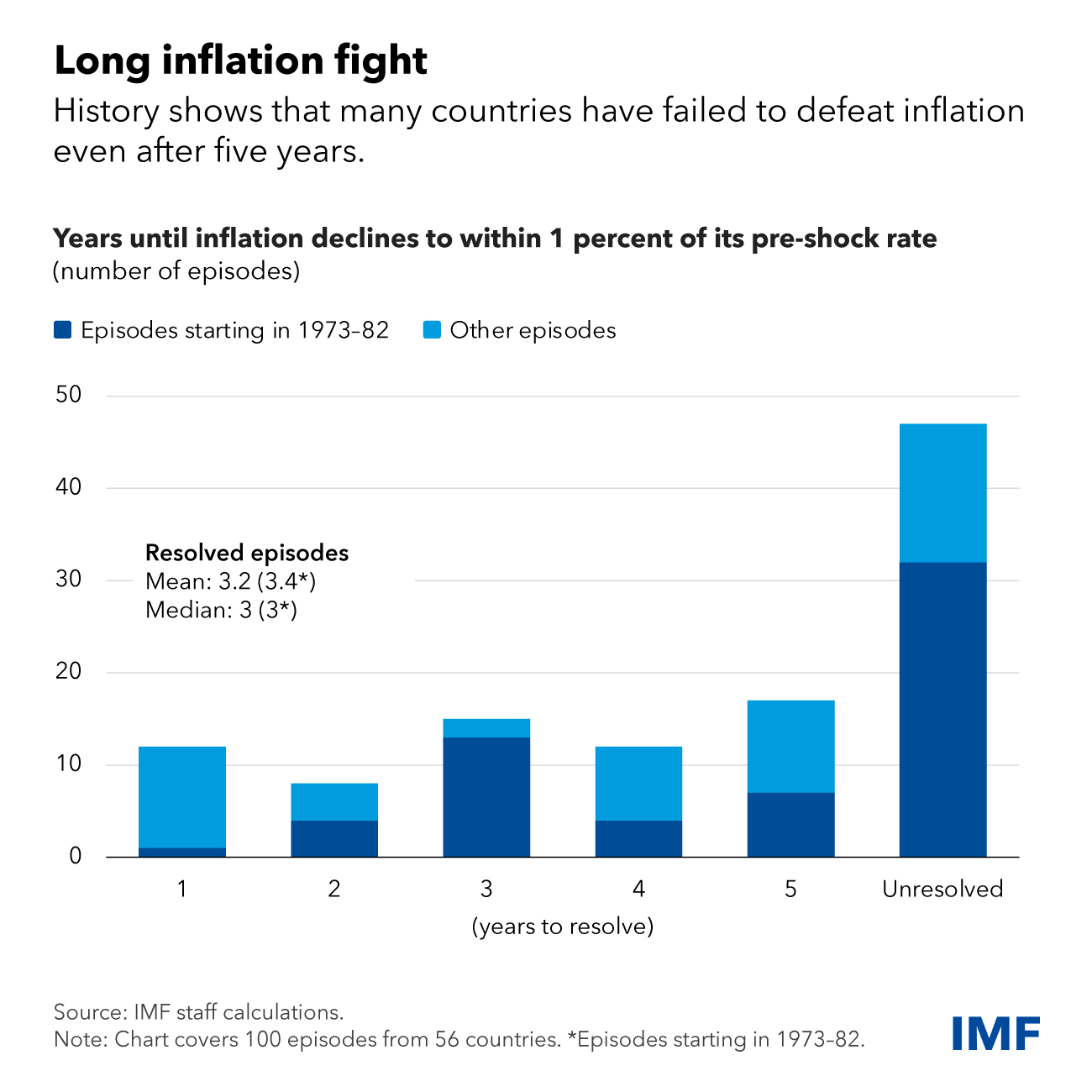

Yet, as we show in a recent paper that looks at 100 inflation episodes worldwide, history is littered with examples of premature celebrations of victory in disinflationary fights—each time with inflation making a comeback.

This is a costly mistake that Europe can and must avoid. Price stability needs to be re-established in the first attempt. And as the effects of tighter monetary policies begin to be felt across Europe, and as criticism inevitably mounts, central banks must not blink. Fiscal policymakers can and should help by lowering still-high deficits to rebuild or preserve fiscal buffers, which will help bring inflation down faster.

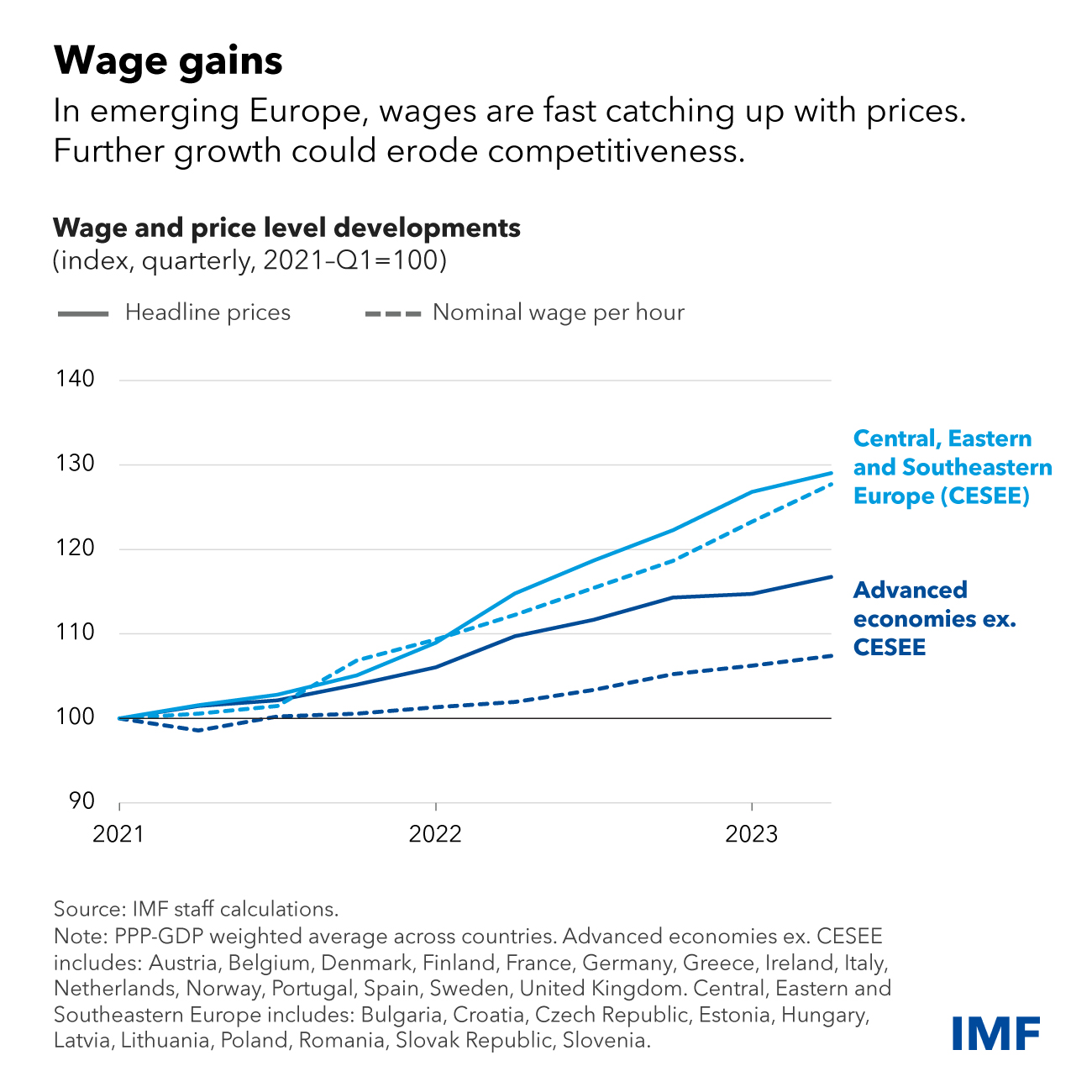

In our projections, we see inflation returning to target sometime in 2025. Before then, nominal wage growth will pick up, recouping some of labor’s lost real income. With tight policies softening domestic demand, firms’ profit margins should compress and help mitigate the impact of faster wage growth on inflation, as we explain in recent research.

There are, of course, risks around our central scenario. Wage growth might outpace our assumptions, driving up labor costs. Profit margins might stay high. And, as the recent spike in oil prices shows, commodity price shocks remain a concern. On the other side of the ledger, if interest-rate increases transmit faster than we anticipate, or more strongly, to demand and to inflation expectations, inflation could decline more rapidly.

Monetary policy should remain data dependent. Under the baseline, this means it should stay the course and remain restrictive in most countries. If inflation comes in much lower or higher, rates would have to adjust. But, in general, during a disinflation effort, it is better to err on the side of doing a little bit more than of doing less in response to an upside surprise.

A time for interest rate cuts will eventually come. When it does, it is best that such cuts do not involve reversals. That time is not now. Urgency also requires patience.

The good news, in the meantime, is that Europe’s jobs markets are strong. Through all the travails of the pandemic, the energy shock, and the sharpest monetary policy tightening in recent memory, European labor markets have proven remarkably resilient. But, with tighter monetary policy now purposefully feeding into sharply tighter credit conditions, and with industry still adjusting to the increase in energy costs relative to their levels a few years ago, some softening of activity is inevitable—even if the slowdown will be partially buffered by steady private consumption on the back of recovering real wages.

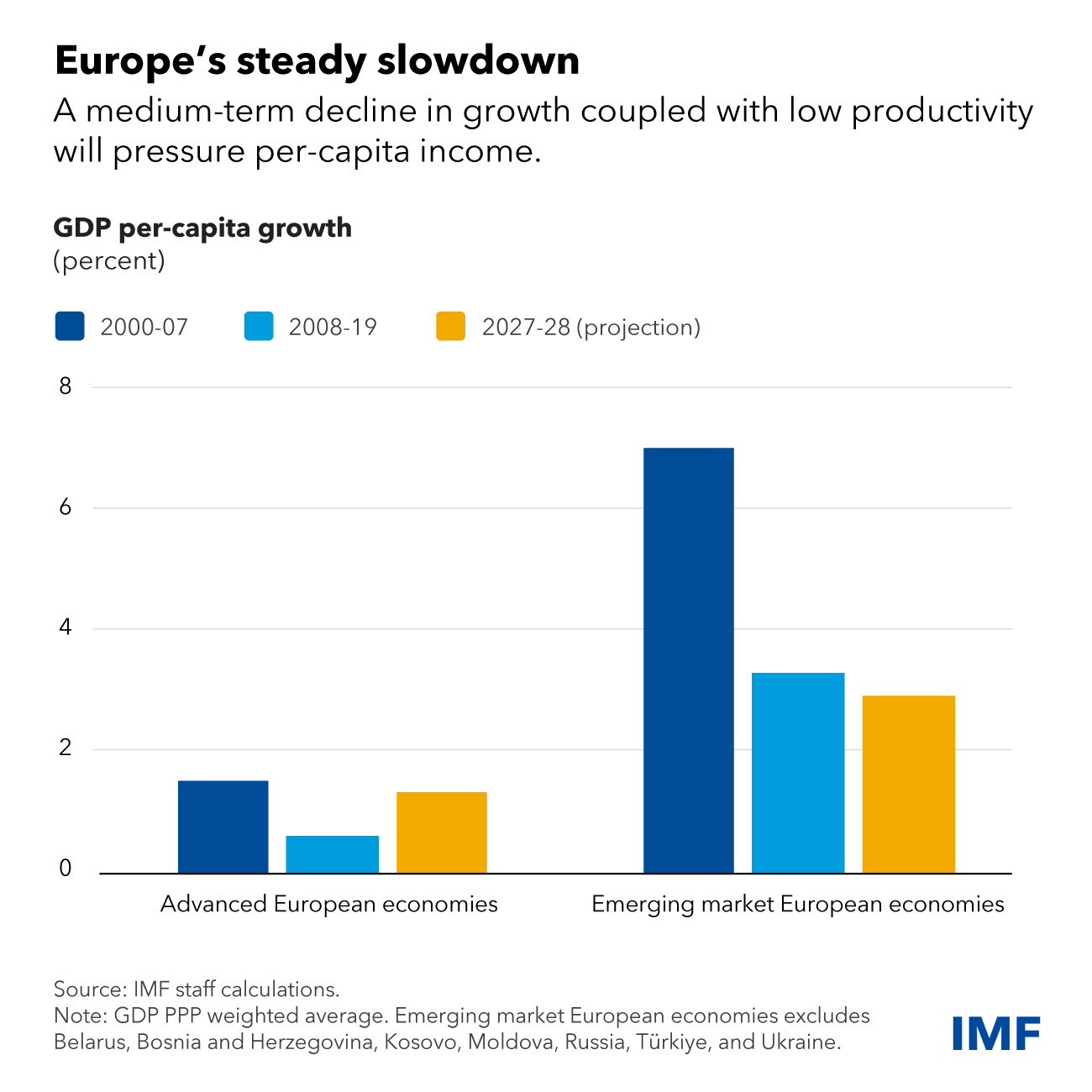

Reflecting a balancing act among these opposing forces, Europe’s economies have indeed slowed this year. We forecast growth of 0.7 percent for 2023 as a whole in advanced Europe, down from 3.6 percent in the post-pandemic rebound of 2022. The slowdown in European emerging market economies (excluding Belarus, Russia, Türkiye, and Ukraine) is expected to bottom out this year at 1.1 percent.

Thereafter, the outlook should improve gradually, with growth in 2024 rising to 1.2 percent in advanced and 2.9 percent in European emerging market economies (excluding Belarus, Russia, Türkiye, and Ukraine).

Amid this modest recovery, some countries will perform better than others. Service-oriented economies such as Croatia, Greece, Spain, and Portugal have benefitted from stronger demand, and are expected to grow by more than 2 percent this year, and their growth next year is expected to remain stronger than in countries with a greater manufacturing base. Energy-intensive manufacturing economies, in contrast, will take longer to recover. Germany is projected to see output contracting by 0.5 percent this year before moderate growth resumes in 2024.

Taking a broader view, huge challenges are in store. In large part due to a slowing of improvements in productivity that began well before COVID, Europe’s growth prospects have been subdued for some time. Well-known factors such as population aging and labor-supply constraints have further stunted growth potential. And, for most of Europe’s emerging market economies, the combination of weak productivity and a loss of business competitiveness on the back of relatively faster wage growth could stall economic convergence with the continent’s more advanced economies.

Global shifts will add to Europe’s longstanding growth problems. The pandemic and persistent energy supply issues added to structural headwinds by disrupting supply chains and raising production costs. Now, European countries are also grappling with structural shifts from geopolitical fragmentation, climate change, and necessary adjustment to new technologies, for example in the car industry.

As major investment needs loom—including to keep our planet livable—it is now time to take difficult decisions. While all countries need to invest in the future, Europe’s high-debt countries in particular need to step up their efforts to replenish fiscal buffers. Higher interest rates and slower growth will make it harder to stabilize debt over the next five years especially for European emerging market economies. Many countries will need to cut spending in non-critical areas and remove tax inefficiencies. Credible upfront commitments to this effect will also help central banks restore price stability.

Improvements in productivity can lift potential growth and help achieve the fiscal goals at lower economic cost. European economies can do a lot in this regard through concerted programs of structural reforms in product and labor markets. Such efforts, too, cannot afford to be left for later.

Europe has shown before that it can rise to big challenges. This time need not be different.