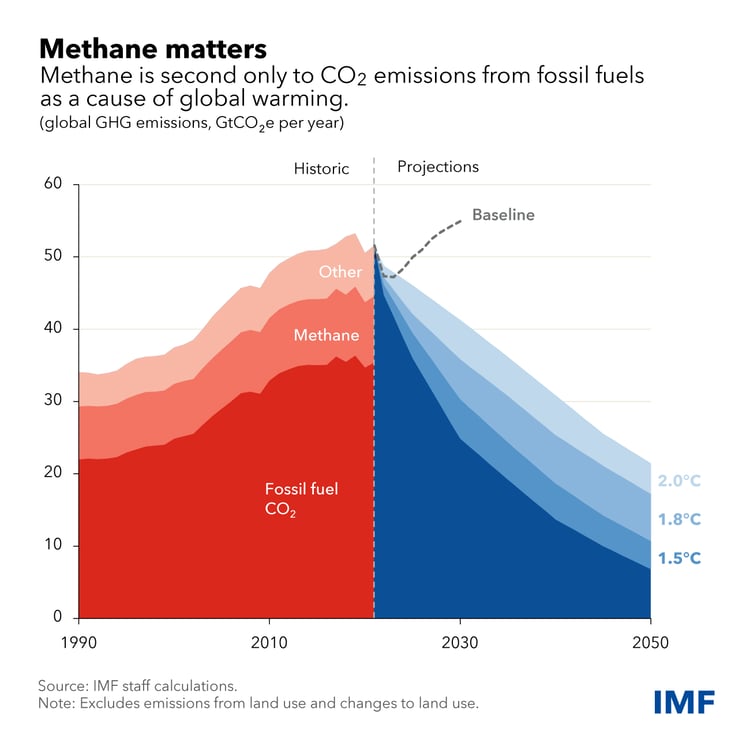

Countries must reduce emissions of greenhouse gases substantially to keep global temperature targets in reach and limit risks of destabilizing the world’s climate. Most attention has focused on carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels, but it is also critical to cut methane emissions—not least because methane has a more powerful near-term warming effect than CO2 and cutting methane emissions would have a more immediate impact on the climate.

As the Chart of the Week shows, global greenhouse gases must be cut by 25 percent to 50 percent from 2019 levels by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5-2 degrees Celsius—the central goal of the Paris Agreement. Reducing methane emissions could lower the stock of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and cut the very scary risks of “tipping points”—when climate change becomes self-perpetuating. This is because methane stays in the atmosphere for only 12 years on average compared with up to a thousand years for CO2.

Methane accounts for about 30 percent of the increase in the global temperature since industrialization and emissions rose by record levels for the second year in a row last year. Most countries pledged to reduce their total greenhouse gases, including methane, as part of the Paris Agreement. In addition, 125 countries have signed a Global Methane Pledge. But commitments—let alone policies—still fall short of what is needed.

Most of the low-cost opportunities for cutting methane emissions are found in the extractive industries, for example fixing leaks in gas pipes, curbing flares from oil wells and coal mines, or installing technologies to capture methane for sale or later use.

Methane emissions from agriculture would likely be reduced if farmers produced more food from plants and less from livestock, or if they switched to more productive cattle herds. Emissions at landfills could also be captured.

Methane fees

Methane fees are a promising and practical instrument to lower emissions, especially if they build off existing business taxes, as we show in a Staff Climate Note published this week. These taxes are common in the extractive sector and, in some cases, agriculture.

Ideally, fees would be introduced in a way that is revenue neutral to limit concerns that they undercut competitiveness. This could be done by lowering taxes on other parts of the business. Another option is “feebates”, under which producers whose emissions are of above average intensity pay high fees, while those below get rebates.

Given challenges in monitoring emissions, fees might be levied based on default emission rates with rebates for firms that can show that their own emissions are less than the default.

We estimate that a global methane fee of $70 per tonne of CO2 equivalent among large emitters would be enough to drive down methane emissions to the levels consistent with keeping global warming below 2 degrees.

An internationally coordinated arrangement focusing on minimum methane prices would be effective from an emission and competitiveness perspective. The arrangement could initially start with key countries that have signed the Global Methane Pledge.

The costs of methane pricing would, however, fall disproportionately on certain emerging market and developing economies. This means that differentiated pricing and international assistance should be important elements of such an agreement.