To stave off risks to recovery, policymakers should focus support on firms that can survive and prepare to restructure or liquidate those that cannot.

Companies entered the COVID-19 crisis with record debts they racked up after the global financial crisis when interest rates were low. Corporate debt stood at $83 trillion, or 98 percent of the world’s gross domestic product, at the end of 2020. Advanced economies and China accounted for 90 percent of the $8.9 trillion increase in 2020. Now that central banks are raising rates to check inflation, firms’ debt servicing costs will increase. Corporate vulnerabilities will be exposed as governments scale back the fiscal support that they extended to stricken firms at the height of the crisis.

Governments face difficult decisions as they manage these risks to the economic recovery. They may need to continue providing financial support to firms that can recover (but cannot raise the private financing to do so) while withdrawing support from firms that are so badly scarred that they should be restructured or liquidated. Financial support should become more focused amid shrinking fiscal space. Effective insolvency systems make economies more resilient, productive, and competitive. Shoring up these systems is critical as there are shortcomings in many important areas at present and countries may need to tackle many cases at once. There is not much time to prepare.

New IMF research takes stock of corporate vulnerabilities and assesses countries’ preparedness to handle large-scale restructuring. It proposes principles to guide the design of policy support for firms that can recover and to facilitate the restructuring of those that cannot.

New IMF research takes stock of corporate vulnerabilities and assesses countries’ preparedness to handle large-scale restructuring. It proposes principles to guide the design of policy support for firms that can recover and to facilitate the restructuring of those that cannot.

Measuring preparedness

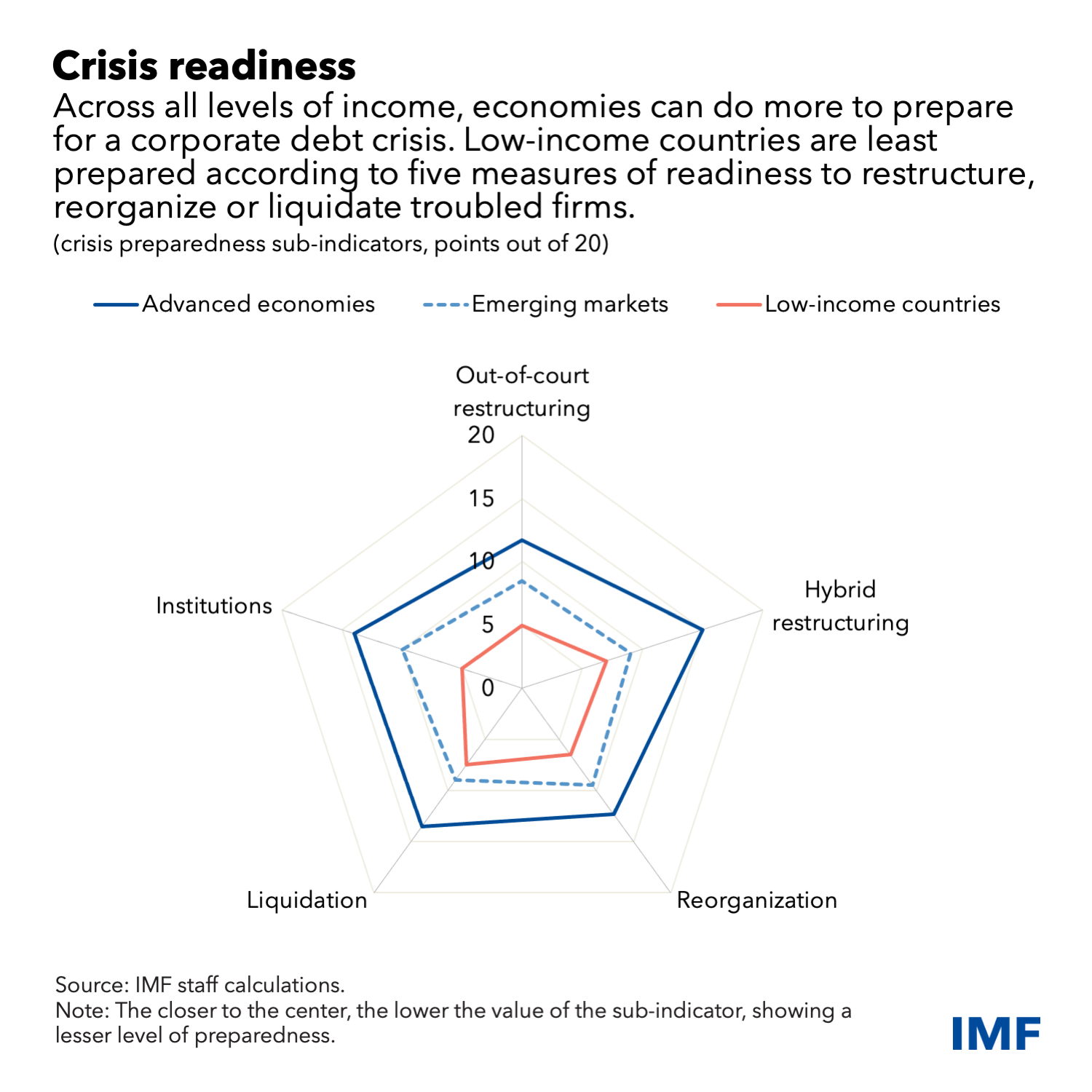

We use a new indicator to measure the extent to which countries’ insolvency and restructuring regimes are prepared for a crisis. Covering 60 economies that account for 91 percent of the world’s GDP and 84 percent of the global population across all continents and levels of development, this indicator offers a representative perspective on countries’ preparedness to handle large-scale corporate crises. The chart below summarizes the five sub-indicators for advanced, emerging market, and low-income economies. The whole dataset is available here.

Corporate vulnerabilities tend to be more pronounced in economies where our indicator shows that there are shortcomings in crisis preparedness. Two-thirds of the emerging market economies whose corporate debt was more vulnerable to adverse economic conditions than the average country also had systems of crisis preparedness that were weaker than average. Almost 40 percent of advanced economies with vulnerable corporate debt had below-average crisis insolvency systems that could struggle in the event of a large number of restructurings. These countries should step up efforts to improve insolvency systems. But all countries can improve crisis preparedness.

Many countries have continued to strengthen their insolvency systems, either with targeted reforms (Brazil, France, India, Korea, Turkey, and the United States) or with broad reforms affecting key elements of their systems (Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom).

Policy principles

What strategies should governments put in place to support viable firms and what legal reforms should they undertake to facilitate debt restructuring, liquidation, and reorganization of distressed companies?

- Policy support schemes should set clear objectives to address specific market failures. This was the case with Australia’s and Norway’s public support programs, for example. They should include strong governance and transparency safeguards to mitigate risks and put in place clear exit plans from the start.

- Burden-sharing and debt-restructuring plans should make use of the access to information and skills of private creditors, as was the case with Mexico during the peso crisis of the mid-1990s and France during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public creditors should actively participate in debt restructuring.

- Insolvency systems should be prepared to handle a large increase in cases, with each country facing different priorities in this area. Countries with limited fiscal space and ineffective insolvency systems should rely more on out-of-court or hybrid restructuring (where the courts play a limited role to support negotiations between debtors and major creditors, and which can be implemented relatively quickly). At the same time, they should tackle deeper reforms over the medium-term to improve legal and institutional frameworks. Countries with fiscal space can provide continued support but should be mindful of the risks of moral hazard and “zombie” firms that survive only with state assistance.

- Banks’ balance sheets should remain sound and transparent. Accounting and regulatory forbearance introduced to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic have increased the potential for hidden nonperforming loans not reflected in banks’ balance sheets. Together with the rise in sovereign debt holdings, bank and government balance sheets have become increasingly intertwined—a phenomenon associated with debt crises. As forbearance ends, the reporting of asset quality should rely on transparent and consistent practices, aided by effective supervision and enforcement. Asset quality reviews can make balance sheets more transparent and support the market for distressed debt—especially after episodes of forbearance. At the same time, banks’ defenses may need to be shored up to absorb the losses from the crisis.

Governments were right to support firms financially through the worst of the pandemic. They recognized the initial large premium on speed over precision and provided rapid support without distinguishing between enterprises that could be saved and those that should not. Now policymakers should calibrate financial support and direct it efficiently to companies that are in need. They should also be prepared to restructure or liquidate badly scarred firms.