As a result, many advanced economies risk experiencing a wave of liquidations that could destroy millions of jobs, damage the financial system, and weaken an already fragile economic recovery. Policymakers should take novel and swift action to alleviate this wave.

Compared to past crises, this time around there is a clearer case for solvency support by governments.

Abundant liquidity support through loans, credit guarantees, and moratoria on debt payments have protected many small and medium enterprises from the immediate risk of bankruptcy. But liquidity support cannot address solvency problems. As firms accumulate losses and borrow to keep carrying on, they risk becoming insolvent—saddled with debt well over their ability to repay.

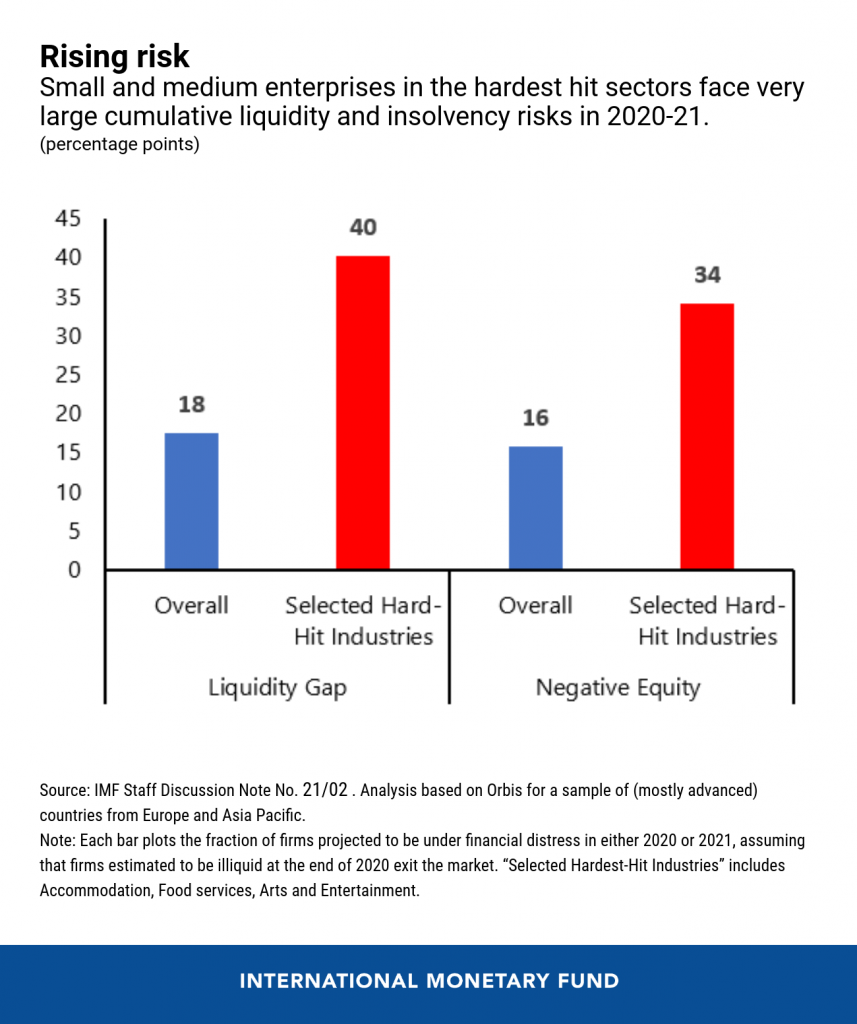

New IMF staff research quantifies this solvency risk, and the findings are concerning. The pandemic is projected to boost the share of insolvent small and medium enterprises from 10 percent to 16 percent in 2021 across 20 mostly advanced economies in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. The increase would be on a magnitude similar to the rise in liquidations in the 5 years after the 2008 global financial crisis, but it would take place over a much shorter period of time. Projected insolvencies put about 20 million jobs at risk (i.e., over 10 percent of workers employed by small and medium enterprises), roughly the same as the total number of currently unemployed workers, in the countries covered by the analysis.

Further, 18 percent of small and medium enterprises may also become illiquid (they may not have enough cash to meet their immediate financial obligations), underscoring the need for continued liquidity support.

The implications for banks are another cause for concern. Rising small and medium enterprise insolvencies could trigger defaults and cause significant write-offs, depleting banks’ capital. In hard-hit countries—mostly from Southern Europe—banks’ capital tier 1 ratios (a key measure of their financial strength) could decline by over 2 percentage points. Smaller banks would be hit even harder, as they often specialize in lending to smaller businesses: a quarter of them could experience a drop of at least 3 percentage points in their capital ratios, while 10 percent could face an even larger fall of at least 7 percentage points.

“Quasi”-equity injections

Compared to past crises, this time around there is a clearer case for solvency support by governments. Because of the sheer magnitude of the problem, the costs of bankruptcies to society far exceed their costs to individual debtors and creditors. For example, if a wave of insolvencies overwhelms the courts, these could fail to restructure viable firms and push them into liquidation instead. Undue losses in valuable productive networks, human capital, and jobs would follow.

In practice, countries with adequate fiscal space, transparency, and accountability could consider quasi-equity injections into small and medium enterprises. Indeed, several are already actively exploring this option, notably in Europe. One approach is for governments to extend “profit participation loans” through fresh loans or conversion of existing ones. These loans would be junior to all other existing debt claims and their payoff could be partly indexed to the firm’s profits. Targeting the right businesses—those insolvent as a result of the pandemic but that have viable business models—is very hard. For this reason, governments might consider conditioning their support on private investors (like banks) injecting equity, which would let the market take a leading role in identifying a firm as a viable business. France, Italy, and Ireland have proposed or enacted policies to incentivize private investors to contribute equity. Support could also be staggered over time, and new tranches deployed only as viability uncertainty dissipates.

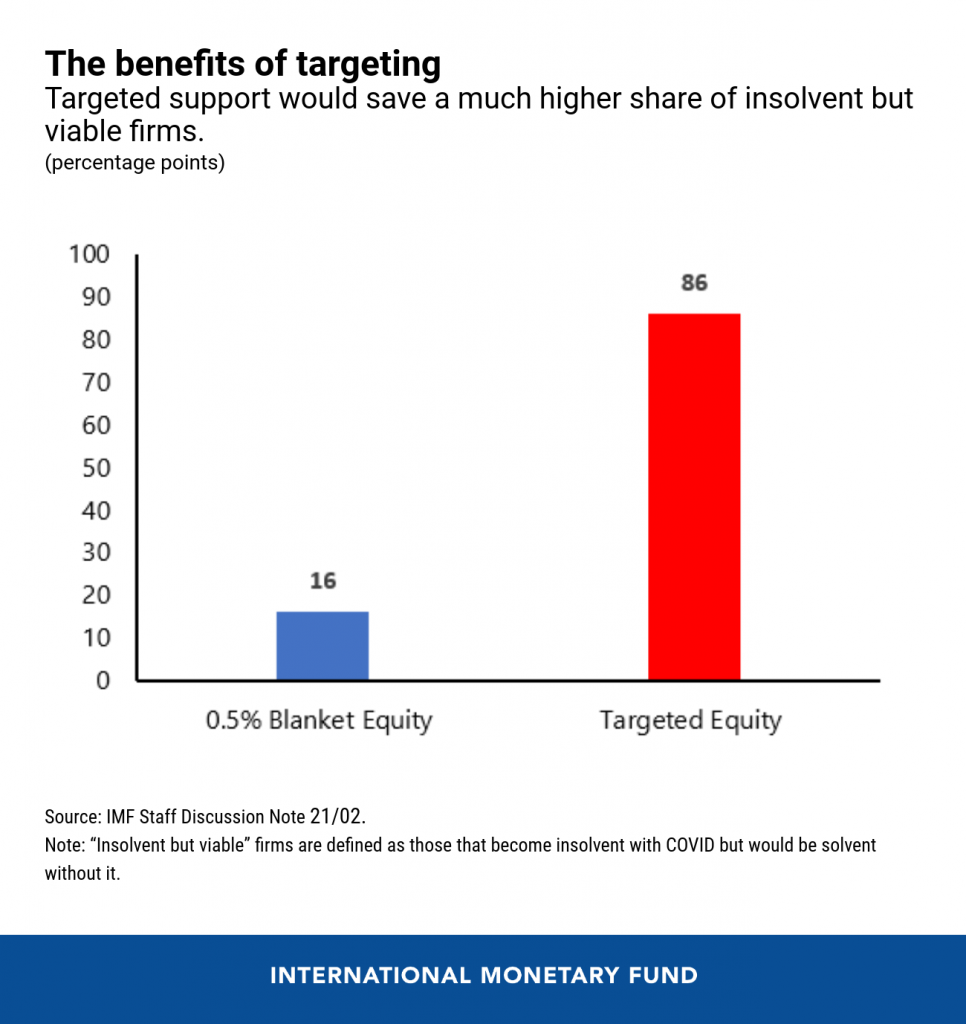

Targeted quasi-equity injections would be far more efficient and powerful than providing support to all firms. Across-the-board (blanket) injections benefit two types of firms that should not receive solvency support: those that do not need it because they are solvent even amid the crisis, and those that would have been insolvent even without the pandemic—that also happen to be less productive. As an illustration, a targeted support program with a budget of roughly half a percent of the overall GDP of the 20 countries analyzed could bring back over 80 percent of the right firms (viable but currently insolvent) to zero net equity (a minimal definition of solvency). This is over four times more than would be achieved under a blanket approach supporting all small and medium enterprises without distinction.

Beefing up insolvency and debt restructuring mechanisms

Even with public support measures, small and medium enterprise insolvencies are likely to rise. Therefore, a comprehensive set of insolvency and debt restructuring tools will be needed for the insolvency proceedings system to cope with the added strain. These tools include dedicated out-of-court restructuring mechanisms, hybrid restructuring, and strengthened insolvency procedures—for instance, simplified reorganization for smaller firms. Since liquidations may be excessive even under well-functioning insolvency procedures, governments could provide financial incentives to tilt the balance towards restructuring.

To secure a strong recovery, governments in advanced economies need to address the risks of small and medium enterprise distress. Combining continued liquidity support, quasi-equity injections and enhanced restructuring mechanisms could go a long way toward that goal.