عربي, 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português, Русский

The COVID-19 pandemic’s destruction of jobs was sure and swift. The lasting effects of the crisis on workers could be just as painful and unequal.

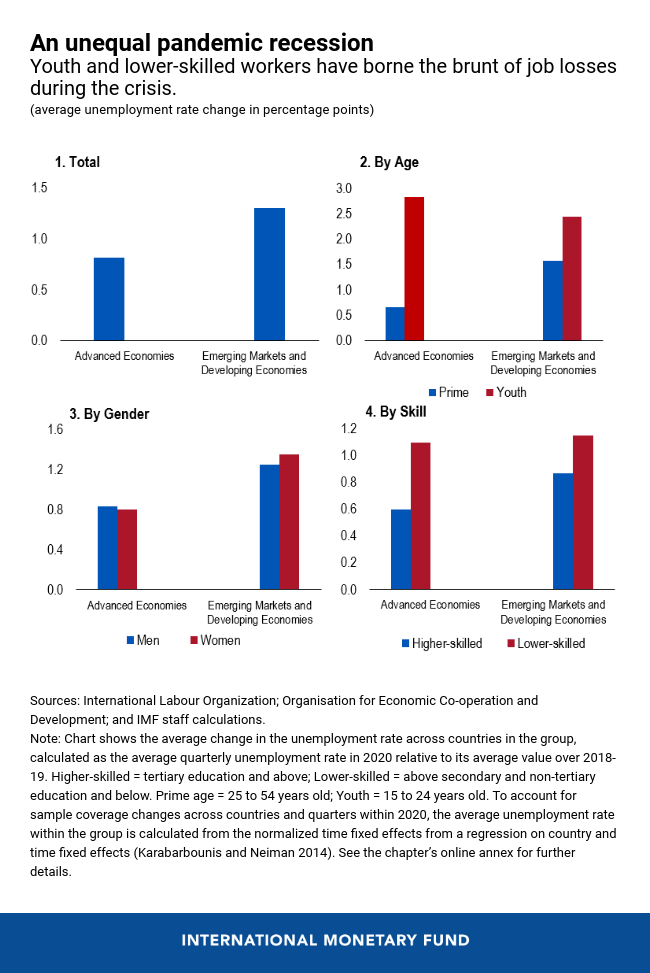

Youth and lower-skilled workers took some of the hardest hits on average. Women, especially in emerging market and developing economies, also suffered. Many of these workers face earnings losses and difficult searches for job opportunities. Even after the pandemic recedes, structural changes to the economy in the wake of the shock may mean that job options in some sectors and occupations permanently shrink and others grow.

The pandemic is likely to inflict sizable costs on the unemployed, particularly lower-skilled workers.

In our latest World Economic Outlook we examine how policies can lessen the pandemic’s harsh and unequal effects. We find that a package of measures to help workers keep their jobs while the pandemic shock is ongoing, combined with measures to encourage job creation and ease the adjustment to new jobs and occupations as the pandemic ebbs, can markedly dampen the negative impact and improve the labor market’s recovery.

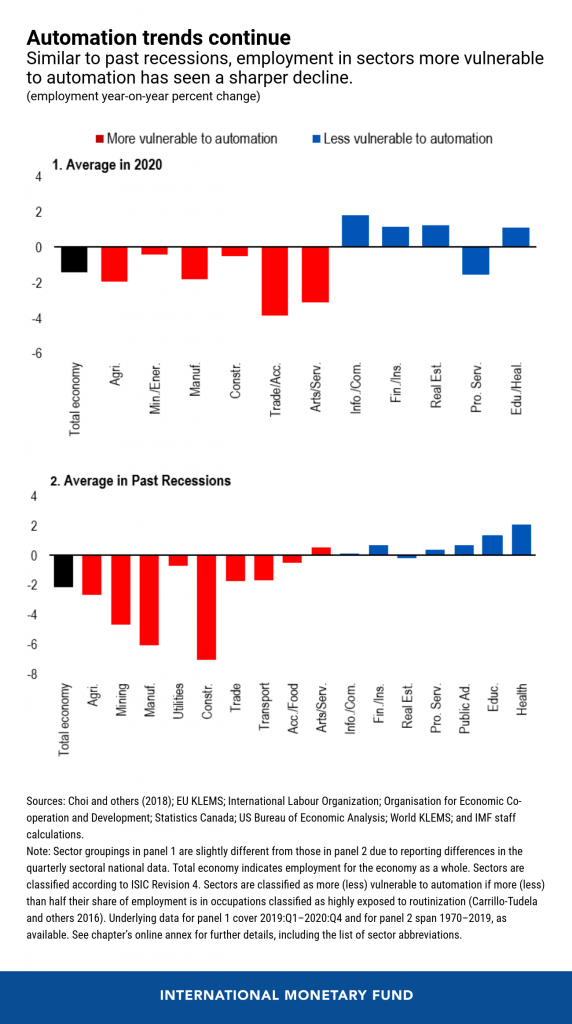

Automation picks up

Jobs that are less skill-intensive and more vulnerable to automation tended to suffer more during the pandemic recession. Although the impacts on specific sectors differed from past recessions, the pandemic has accelerated preexisting employment trends, reinforcing a shift away from employment in sectors and occupations more vulnerable to automation.

Among those sectors that have shrunk the most from the crisis are hotels and restaurants (accommodation and food) and wholesale and retail stores (trade). Social distancing and behavioral changes induced by the pandemic intensified the employment drops in these sectors typically seen in past downturns. By contrast, the information technology & communication and finance & insurance sectors have actually seen employment growth last year. Many of the more impacted sectors—often with fewer jobs amenable to remote work—tend to employ higher shares of youth, women, and the lower-skilled, contributing to the unequal effects across worker groups.

A steep climb back

Evidence from past recessions suggests that the pandemic is likely to inflict sizable costs on the unemployed, particularly lower‑skilled workers. After unemployment spells, workers often have to switch occupations to find a new job, which tends to come with a pay cut. On average, unemployed workers finding work in a new occupation experience a large average earnings penalty of about 15 percent compared to their previous earnings.

Lower-skilled workers experience a triple whammy: they are more likely to be employed in sectors more negatively impacted by the pandemic; are more likely to become unemployed in downturns; and, those who are able to find a new job, are more likely to need to switch occupations and suffer an earnings fall.

Finding the right balance

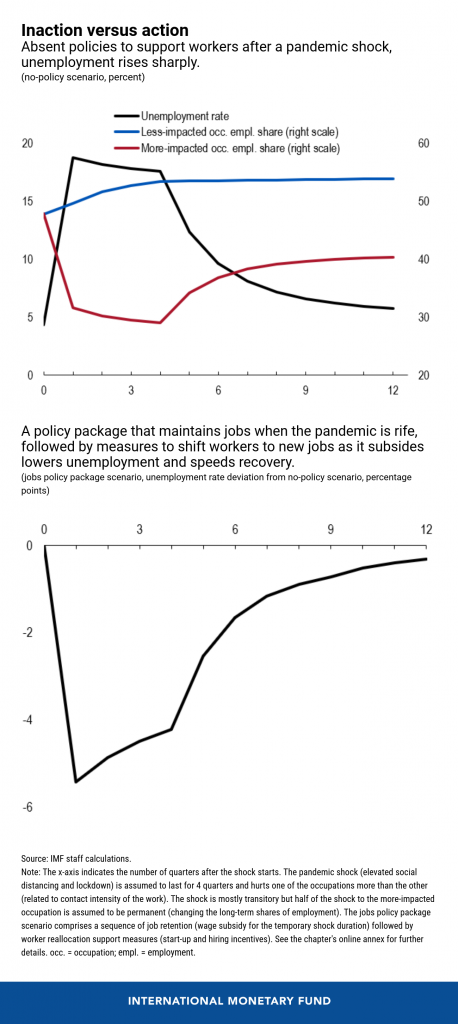

Our analysis shows how the appropriate policies can be extremely powerful at reducing scarring and reducing the unequal impacts across workers. In the absence of measures to bolster the labor market (a no-policy scenario), an economic shock brought on by a pandemic that hits occupations asymmetrically leads to an enormous and rapid rise in unemployment and a grinding adjustment as economic conditions gradually improve.

If job retention and worker reallocation support are used as part of a package, then the hit to employment is less severe and workers and firms are able to adjust faster. This mix of policy support also disproportionately benefits lower-skilled workers, who tend to suffer more from the pandemic’s larger impacts on contact-intensive but lower productivity work. Job retention measures (such as short-term work schemes—like Germany’s Kurzarbeit scheme—and wage subsidies—like the new US Paycheck Protection Program) help preserve jobs against the initial shock of the pandemic, when social distancing is high, lowering unemployment about 4 ½ percentage points below what it would have been without such support. As the pandemic subsides, worker reallocation policies—such as incentives to start new businesses and hire workers, assistance to help match workers to new jobs, and (re)training programs—can help ease the adjustment to the more permanent effects of the pandemic on the structure of employment. Targeting some policy measures toward more impacted populations (such as youth) could also hasten the recovery.

Policymakers will need to take careful account of the path of the pandemic (including cases and deaths, the extent of distancing measures, and rollout of vaccines) in deciding whether the economy can withstand a shift from measures that mainly support existing jobs toward policies that aim to expedite workers’ movements to growing sectors and occupations. The right balance of policies can reduce the unequal impacts of the pandemic across workers and encourage a speedier labor market recovery.

Based on Chapter 3 of the World Economic Outlook, “Recessions and Recoveries in Labor Markets: Patterns, Policies, and Responses to the COVID-19 Shock,” by John Bluedorn (lead), Francesca Caselli, Wenjie Chen, Niels-Jakob Hansen, Jorge Mondragon, Ippei Shibata, and Marina M. Tavares, with support from Youyou Huang, Christopher Johns, and Cynthia Nyakeri.