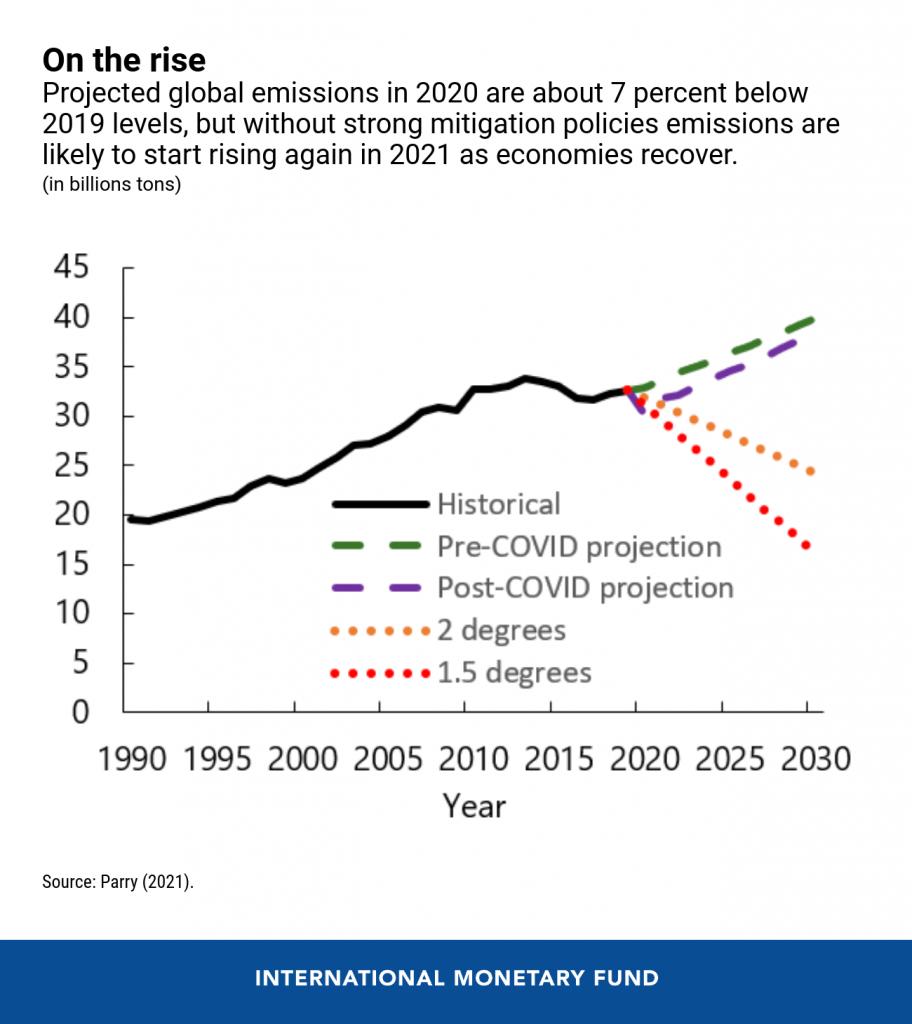

The United States intends to do its part. Its climate plan pledges US carbon neutrality by 2050, with a 2030 emissions target to be announced shortly.

The United States will need to act decisively to help deliver the global emissions reductions needed over the next decade.

The plan envisions stronger energy efficiency standards, clean technology subsidies, and $2 trillion of public funding over ten years for clean energy infrastructure and critical technologies, such as green hydrogen.

This blueprint is an excellent start. Our new research highlights specific fiscal actions that would help curb emissions and broaden support for policies to tackle climate change.

The case for carbon pricing

Take, for example, the implementation of a carbon charge. A nationwide scheme for pricing carbon dioxide emissions—for instance, a carbon tax—would substantially lower the economic costs of attaining emissions targets. The tax would increase the price of carbon-intensive fuels and electricity, thereby providing incentives to reduce energy use and shift toward cleaner fuels across all sectors. It would also help spur clean technology investments. Carbon pricing also mobilizes revenue, reduces deaths from local air pollution, and is straightforward to administer. The government could integrate carbon charges into federal gasoline and diesel taxes, for example, and extend them to coal, natural gas, and other petroleum products.

Such a policy would be highly effective in terms of reducing emissions. To illustrate, a carbon tax rising to $50 per ton by 2030 would cut US carbon dioxide emissions 22 percent. In addition, it would raise revenue by about 0.7 percent of GDP per year.

Momentum on carbon pricing is building internationally. Emissions trading schemes have recently emerged in China, Korea, and Germany, while Canada is raising its carbon price to $135 by 2030. Resistance to carbon pricing in the United States remains strong—nine carbon tax bills since 2018 have failed to make progress in Congress—but there are strategies for broadening support.

A key sensitivity is the potential impact on energy prices—a $50 carbon tax would increase the future price of gasoline, electricity, and natural gas by 15, 40, and 100 percent respectively. And the resulting burden on households is initially regressive—it would amount to 1.6 percent of consumption for people in the bottom fifth of incomes, but only 0.9 percent for those in the top fifth. But that’s before using the carbon tax revenue to compensate those most affected by the measure: compensating those with incomes in the bottom 40 percent would require only 25 percent of the revenue. The remainder could be channeled to other productive investments, such as clean infrastructure spending, or cuts in burdensome taxes on employment.

The climate plan also proposes a border carbon adjustment. Under this mechanism, certain emissions-intensive goods imported from countries that do not have a carbon price equivalent to that of the United States would have to pay a surcharge to make up the difference. Conversely, a US-made product exported to such a country could get a refund for the carbon fee associated with its carbon footprint. The European Union is moving ahead with this mechanism, and other countries are considering it . If the United States introduced carbon pricing, a proposed border carbon adjustment could preserve the competitiveness of US steel, aluminum, and other energy-intensive producers, at least until countries coordinate over carbon pricing.

Under any emissions mitigation strategy, the clean energy transition will provide many opportunities in sectors such as technology and renewable energy, while negatively impacting some existing industries: measures will be needed for assisting vulnerable workers and regions in these sectors.

Reinforcing incentives at the sectoral level

To the extent that carbon pricing remains constrained by politics or other factors, it will need reinforcing with other instruments. A promising approach is feebates, which impose a fee on products or activities with high carbon dioxide emission rates and provide a rebate to products or activities with low carbon dioxide emissions rates.

For example, a feebate for transportation would apply a tax on new vehicles equal to the product of a carbon price, the difference between the vehicle’s emissions per mile and the fleet average, and the average lifetime mileage of a vehicle. A feebate with a shadow price of $200 per ton of carbon dioxide would provide a subsidy of $5,000 for electric vehicles and a surcharge of $1,200 for a vehicle with fuel economy of 30 mpg. Subsidies for clean vehicles would decline (and taxes for high emission cars would rise) as the average emission rate declines over time. Analogous schemes could be applied to other sectors, including power generation, industry, buildings, forestry, and agriculture.

A combination of feebates might be more palatable than carbon pricing, as it would avoid a large increase in energy prices (since there is no pass through of carbon tax revenues in higher energy prices). At the same time, it would not promote some of the demand responses of carbon pricing: for example, unlike higher fuel taxes, feebates do not encourage people to drive less. Feebates do, however, tend to be more flexible and cost effective than regulations, and (unlike clean technology subsidies) they avoid a fiscal cost.

International coordination is key

The US plan seeks to scale up mitigation ambition among large emitting countries. International coordination can help by providing reassurance against concerns about effects on competitiveness and countries reneging on their mitigation commitments. A promising mechanism to complement countries’ Paris Agreement pledges would be an international carbon price floor, where large emitting countries agree to implement a minimum price on their carbon emissions. The price floor could be designed equitably with stricter requirements for advanced economies, assistance for lower-income economies, or both. It could also be applied flexibly to accommodate alternative approaches with equivalent emission impacts in countries where pricing is difficult.

As the world’s second largest emitter, the United States will need to act decisively to help deliver the global emissions reductions needed over the next decade. The US administration should seize this chance to adopt novel approaches that can move the climate agenda forward on all fronts.