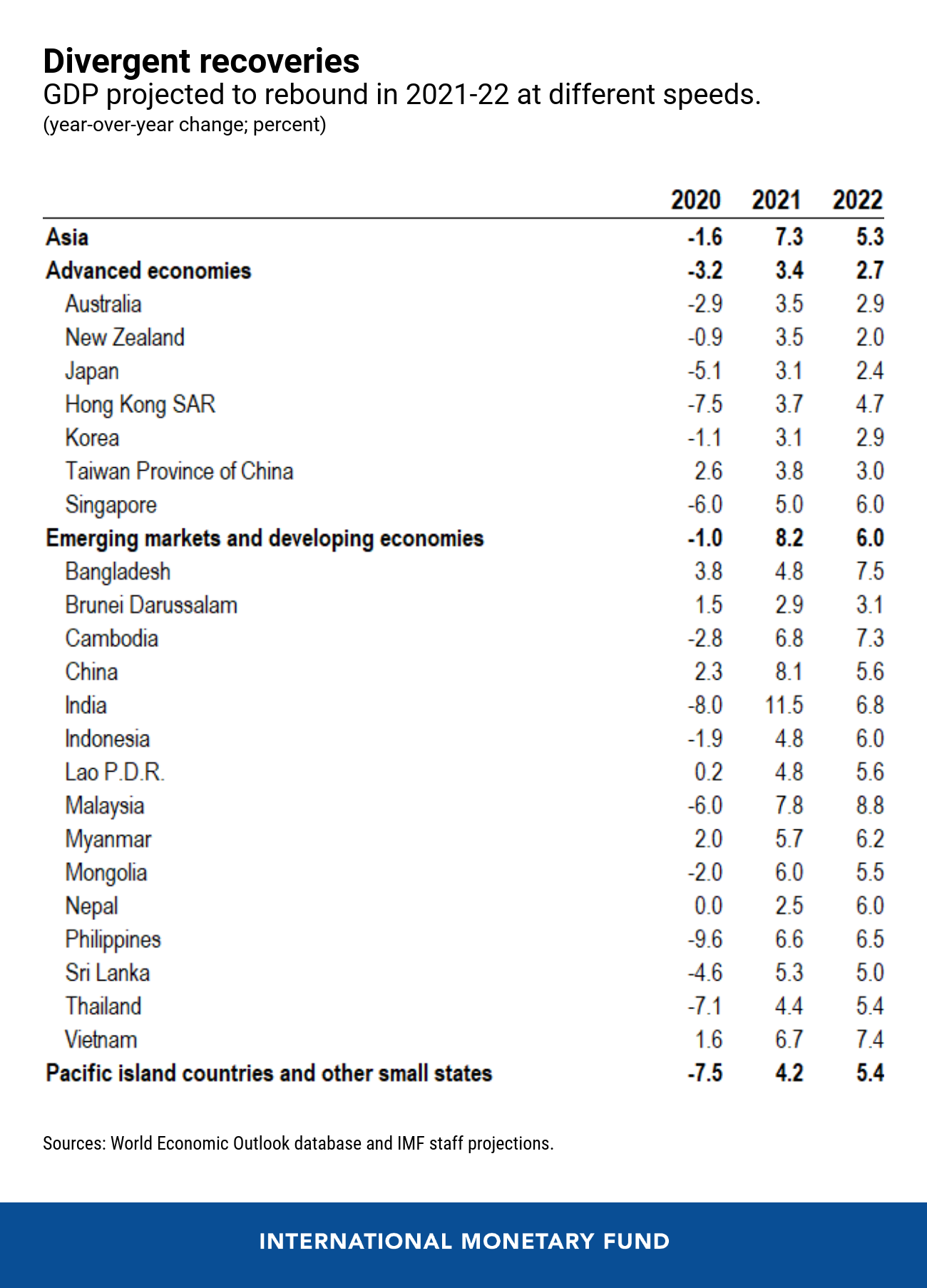

In the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook Update, we upgraded our growth estimate for 2020 by 0.7 percentage point from our previous forecast in October, to a contraction of 1.5 percent—in regional terms, a better outcome than other parts of the world. This is largely driven by stronger-than-expected performance among advanced economies in the region, as well as some large emerging market economies such as China, India, Malaysia, and Thailand.

The expectation is for strong growth in Asia-Pacific in 2021 and 2022; but the aggregate figures mask an enormous range of output losses.

Growth outturns in the fourth quarter and higher-frequency economic indicators for industrial, trade, and retail activity point to a strengthening recovery. Output is projected to grow by 7.3 percent in 2021 and 5.3 percent in 2022 but, even if such a reality materializes, output losses from the pandemic will be significant nonetheless.

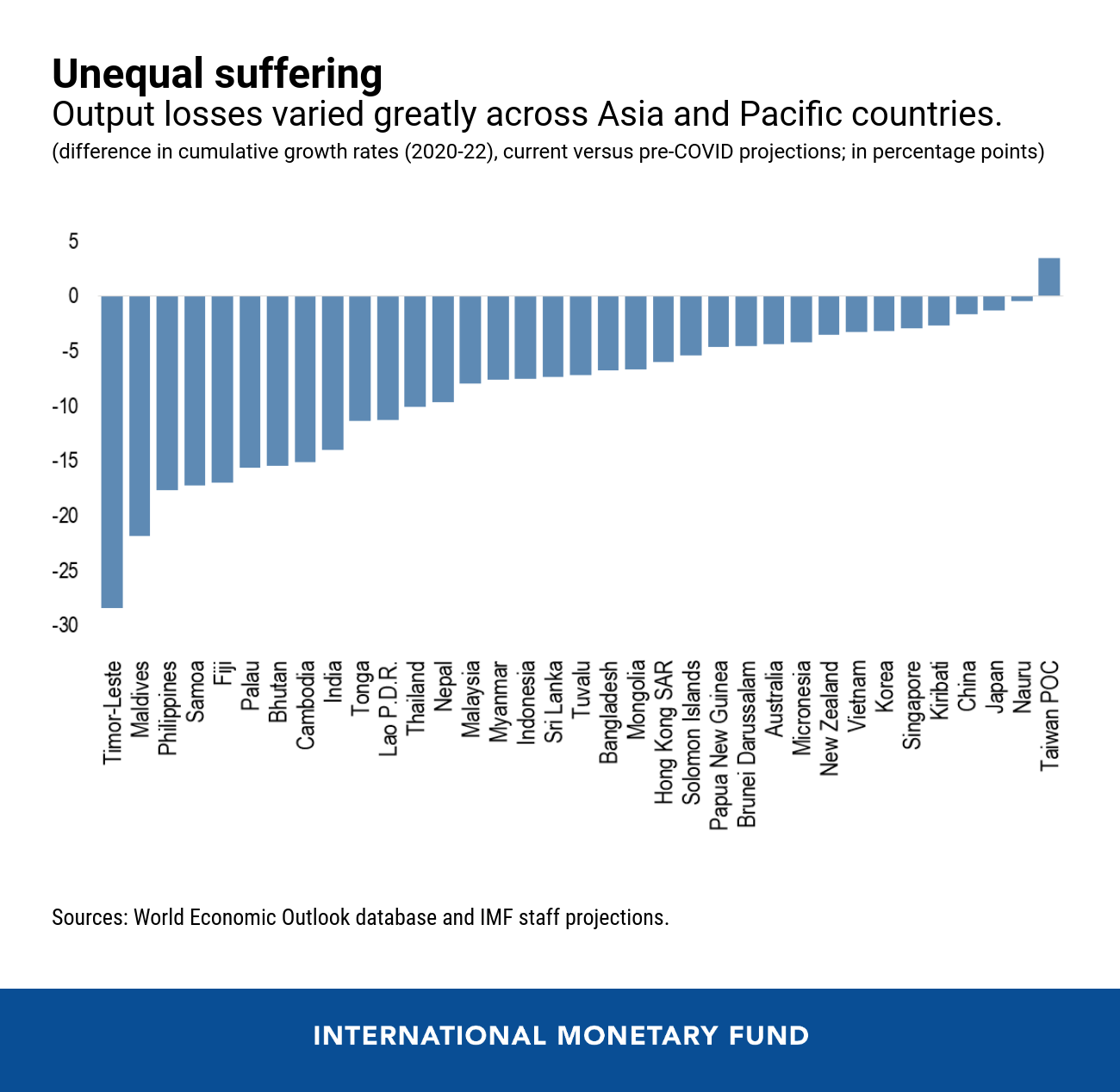

The aggregate figures mask an enormous range of output losses across economies, from close to zero in China, Japan, and Taiwan PoC to more than 20 percentage points in the Philippines and even 30 points in East Timor. The divergence is especially sobering for the Pacific islands and other low-income countries in the region, where lives and livelihoods will depend on additional international support.

Understanding the Divergence

Divergence is evident when comparing the IMF’s pre-pandemic (October 2019) forecasts with the current cumulative GDP growth projections for 2020, 2021, and 2022 (respectively, the years of impact, recovery, and when herd immunity is expected). Our recent research as well as country experiences identify four main reasons for the large disparity.

Health factors such as the effectiveness of containment measures and the human toll of the disease. The early implementation of stringent containment measures—such as in Australia and Vietnam—proved crucial in flattening the pandemic curve, ensured that medical systems were not overwhelmed and fatalities were reduced, laying the foundation for the recovery. Meanwhile, the rollback of containment measures only after the stabilization of outbreaks and establishment of strong testing and tracing regimes—for example, in China and Korea—were key to boost confidence and pave the way for a stronger rebound in economic activity and better health outcomes.

The magnitude and effectiveness of policy support. Extensive monetary and fiscal support—Japan and New Zealand being notable examples—has helped to mitigate the economic effects of containment measures and facilitated the resumption of activity. Fiscal measures targeted at the most vulnerable households (for example, consumption coupons in Korea and cash transfers to casual workers in Australia) also helped support incomes while affected workers remained at home during lockdowns, reducing the number of infections and laying the ground for higher medium-term growth.

Countries’ economic structure, including the dependence on tourism and contact-intensive service sectors. Containment has hurt all sectors, but tourism has been affected the most. Given the employment composition in the tourism sector, informal and migrant workers, particularly women and youth, have suffered disproportionately from diminished opportunities and lack of access to social safety nets. These effects have been particularly important for the Pacific islands and other countries heavily reliant on tourism, such as Cambodia, the Philippines, and Thailand.

Other structural factors such as informality have exacerbated the economic cost of lockdowns and weighed on the recovery. In the Philippines, the high concentration of economic activity in the Manila metropolitan area, weak transportation infrastructure, low capacity in the health sector, poverty, and a high share of informality, have together significantly complicated enforcement of containment measures and the ability to provide targeted support to the most vulnerable.

The way forward

While the divergent results from last year are history, they are not destiny. Looking forward, four policy priorities will help to shape a better future.

- Ensuring that vaccines are widely available to end the pandemic everywhere. Speedy distribution and availability of effective therapies are key to generate stronger consumption, investment, and employment recoveries, with firms hiring and expanding capacity in anticipation of rising demand. In this respect, support to developing countries in terms of funding, logistics, and administration is crucial to address divergent recoveries and close gaps between developing and advanced economies.

- Policies to support affected workers and businesses should continue until recovery is entrenched and there are signs of a self-sustained revival in private domestic demand. High levels of uncertainty call for a slower withdrawal while remaining vigilant about debt sustainability and financial sector risks.

- Economic transformation. As containment measures are eased, policies to stimulate private sector demand are likely to become more effective and can replace broad sectoral assistance. Building greener, more inclusive, resilient, and digital economies must take center stage once the pandemic is under control. To encourage reallocation, “trampoline” policies, such as job counseling and retraining, should be used alongside safety nets to protect the most vulnerable.

- Financial support from the international community is desperately needed to reverse the increasing divergence between rich and poor countries. Many low-income economies, including the Pacific island countries, have been hit particularly hard by the crisis, have little policy space to respond, and will require financial assistance for the foreseeable future. Global cooperation via the G-20 Common Framework can help clear a path for countries to restructure unsustainable debt and grow.

The Asia-Pacific region went into this crisis first and many of its economies are emerging from it first as well. Indeed, several Asian countries are recognized as having responded highly effectively to the pandemic. Yet the magnitude of output loss is still unprecedented and the weakening of labor force participation and diminished job prospects for youth and women suggest that significant scarring remains likely. All this suggests policy leadership remains critical in the period ahead.