Martin Mühleisen, Vladimir Klyuev, Sarah Sanya

عربي, 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português, Русский

The coronavirus crisis is a crisis like no other, and for emerging market and developing economies (EMDE), it has triggered a policy response like no other, both in scope and magnitude.

Despite their diversity, and in some cases, strained resources, this large group of countries—consisting of emerging markets and low-income countries—have bolstered the provision of health services and extended unprecedented support to households, firms, and financial markets. While limited policy space has kept the response at a smaller magnitude than in advanced economies, some even managed to help other countries.

A whole new world

Economic activity in EMDEs has decelerated at a pace unseen in at least 50 years as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic ravages the global economy. Several countries are experiencing a sharp decline in trade and capital flows, and the impact of an unprecedented decline in oil and other commodity prices. A spate of sovereign downgrades has occurred.

The IMF’s Policy Tracker summarizes key policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and within these responses, there are some common threads.

Fiscal policy to save lives and protect livelihoods

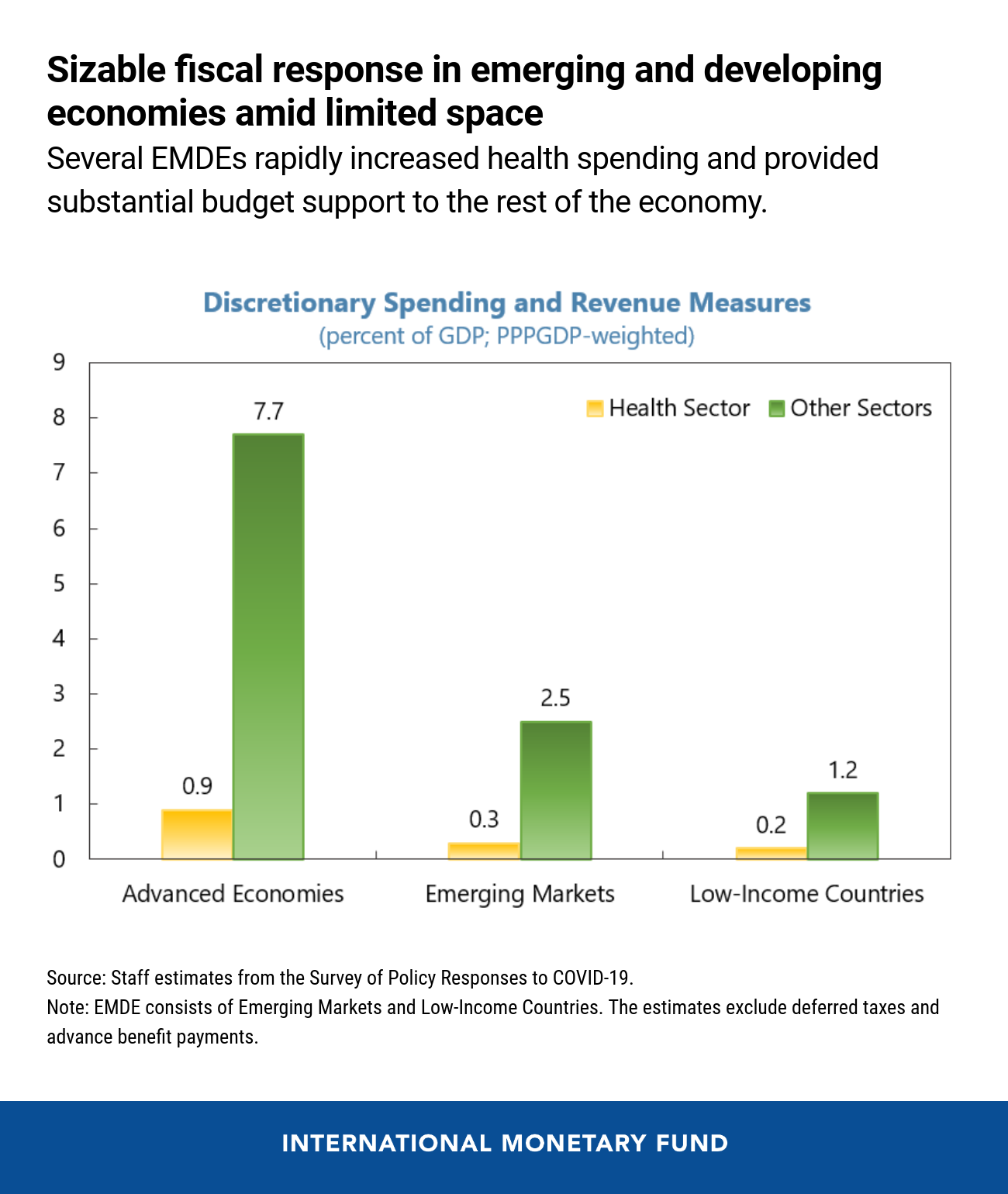

Fiscal policy has been at the forefront of the EMDE response. Within EMDEs, the health crisis is necessitating massive health spending, though this increase has been dwarfed by the resources needed to support the broad economy. Countries have provided loans, guarantees, and tax breaks to corporations and SMEs, and extended support to vulnerable households with higher unemployment benefits and subsidies on utility prices.

Financing for these new measures emerged from a variety of sources, including borrowing, drawing down buffers, reprioritizing within existing budgets, and multilateral support.

Some economies entered this crisis in a vulnerable state with already sluggish growth, high debt levels and limited fiscal space to support the health sector and the flagging economy. About half of all low-income countries were considered in debt distress or at a high risk of debt distress even before the crisis, as assessed by the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Framework. Partly reflecting these constraints, the total discretionary fiscal response to the shock has been lower (although still sizeable) in both emerging market and low-income economies at 2.8 and 1.4 percent of GDP respectively in extra spending and tax reductions, compared with 8.6 percent of GDP in advanced economies.

Monetary and financial sector support—an anchor for stability

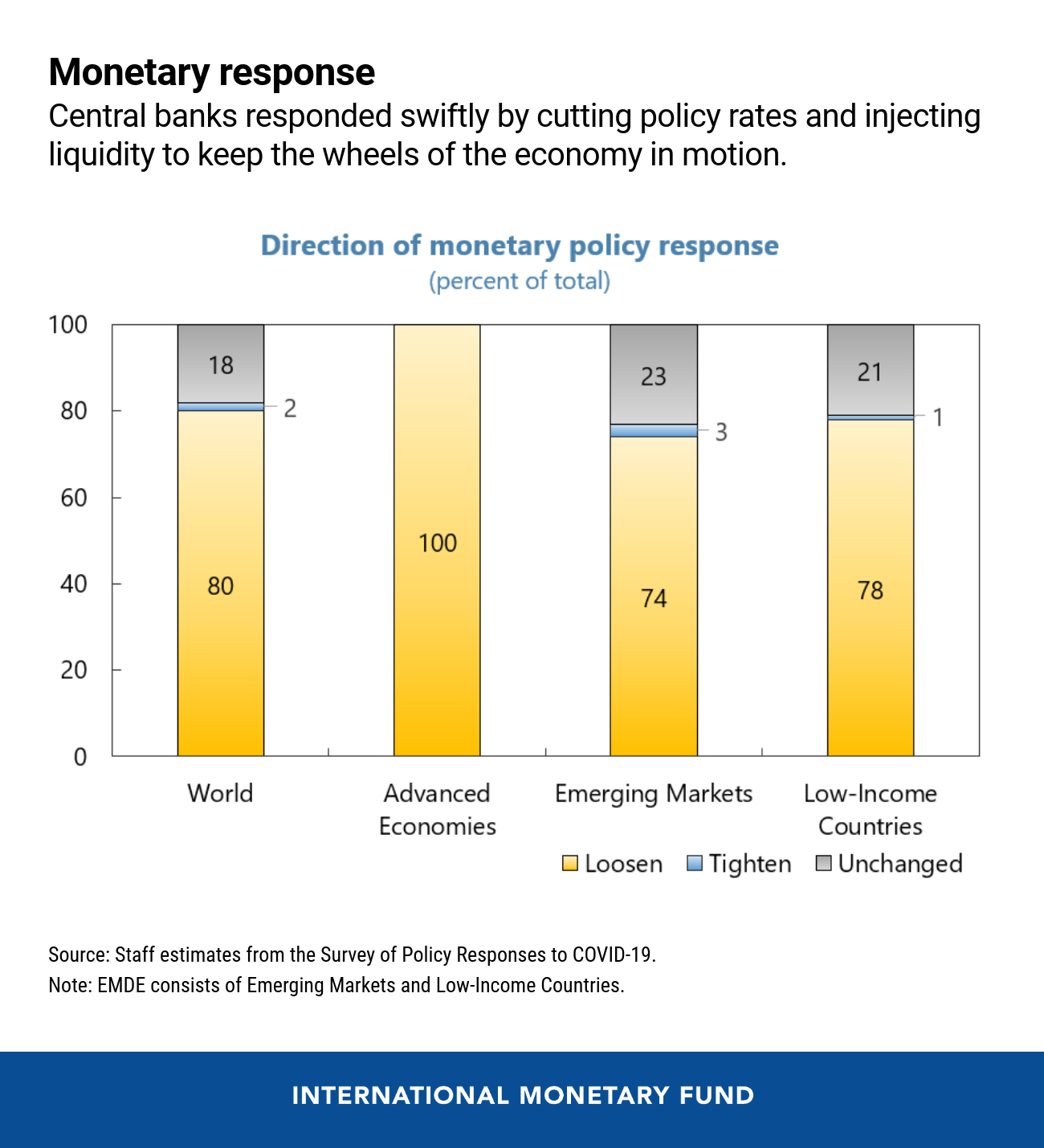

EMDE central banks cushioned the impact of the shock on credit conditions through policy rate cuts and liquidity injections. Unlike previous episodes of capital outflow pressures—including the early stage of the Global Financial Crisis—most emerging market economies lowered policy rates (most of them by 50 basis points or more) rather than raising them. This could be attributed to lower inflation pressures and generally more credible monetary policy frameworks.

Like many advanced economies, some emerging markets possess little room to cut interest rates further and implemented “unconventional monetary policy” responses—such as purchases of government and corporate bonds.

Regulatory restrictions including on liquidity and loan classification have been loosened to help banks play a more supportive role during the pandemic.

In addition, some countries including China and Colombia have relaxed select macroprudential measures—constraints on lending and borrowing introduced to contain excessive loan growth, and the build-up of systemic risk in the financial sector that can occur in good times. Now, a relaxation can support the supply of credit to hardest-hit individuals and economic sectors.

Staying flexible

Currencies of EMDEs with flexible exchange rates have depreciated in response to outflow pressures and heightened risk aversion—over 25 percent in a few cases.

Many economies took advantage of their buffers to offset some of the pressure by intervening in the foreign exchange market and drawing down their international reserves. A few countries eased existing capital controls on inflows, while recourse to measures to curb capital outflows has been very limited.

Digitization—a lifeline to protect the vulnerable

Countries such as Bolivia and Indonesia are using digital technology to counteract the sudden economic distress on households and small and medium-sized enterprises, and to limit the spread of the disease by encouraging cashless payments. Others, such as Colombia and Kenya, are ensuring affordable access to digital (easing restrictions on internet access) and financial services (mobile money and electronic payments charges). Zambia provided subsidies to small-scale farmers through the digital platform.

Digital solutions have helped target relief to the vulnerable and enhance the effectiveness of traditional macro policies.

Managing supply disruptions

As the pandemic and prolonged lockdown hampered global supply chains, many countries took steps to ensure food security and continued access to medical supplies, mostly on a temporary basis. For example, several countries introduced price controls and issued regulations against price gouging for basic food items and medical supplies. Some eased import controls. Unfortunately, in several cases restrictions were introduced on the exports of food and pharmaceuticals.

International solidarity—helping countries reach further

In response to the COVID-19 shock, the global financial safety net has been activated and strengthened. The U.S. Federal Reserve has established new swap lines with central banks in several major advanced and emerging economies.

The G-20-led debt moratorium initiative, and financial assistance from the IMF and other institutions are helping EMDEs cope with the challenges. The IMF has quickly provided emergency assistance to more than 60 countries. Further, as demand for liquidity increased, the IMF recently established a new Short-term Liquidity Line as part of its COVID-19 response to augment its lending toolkit. In addition, massive liquidity provision by major advanced economy central banks, while directed primarily at domestic financial conditions, has also alleviated pressures on emerging market and developing economies.

At the same time, EMDEs are also extending assistance to each other and other countries in need. In particular, Regional Development Banks are providing support for private sector enterprises, trade finance and continued access to medical supplies. Examples of bilateral assistance include Albania, which dispatched a team of doctors to Italy, and Vietnam, which donated medical supplies to neighboring countries as well as advanced economies.

EMDEs have been heavily affected by the COVID-19 shock and market reaction that it triggered. The analysis of the IMF Policy tracker shows an extraordinary policy response, bolstered by innovation and international cooperation. In this unprecedented and fast-moving situation, countries can benefit from learning from their peers, and the Fund is committed to collecting and sharing best practices and incorporating this data into its own analysis to continue to assist our membership.