Escalating trade tensions are taking a toll on the global economy and are partly responsible for the recent downward revisions to our growth forecasts for 2019-20.

Facing sluggish growth and below-target inflation, many advanced and emerging market economies have appropriately eased monetary policy, yet this has prompted concerns over so-called beggar-thy-neighbor policies and fears of a currency war. In this blog post, we discuss the implications of recent policy actions and proposals and offer alternative ways to address concerns over trade imbalances that are much more supportive of global growth.

Higher bilateral tariffs are unlikely to reduce aggregate trade imbalances.

Exchange rates can’t do it all

Monetary easing can help stimulate domestic demand, which in turn benefits other countries by increasing demand for their goods. The concern, however, is that monetary easing also weakens a country’s exchange rate, making exports more competitive and reducing demand for other countries’ imports as they become more expensive—a phenomenon known as expenditure switching. With conventional monetary space limited for some advanced economies, this currency channel of monetary easing has received considerable attention. But one should not put too much stock in the view that easing monetary policy can weaken a country’s currency enough to bring a lasting improvement in its trade balance through expenditure switching. Monetary policy alone is unlikely to induce the large and persistent devaluations that are needed to bring that result.

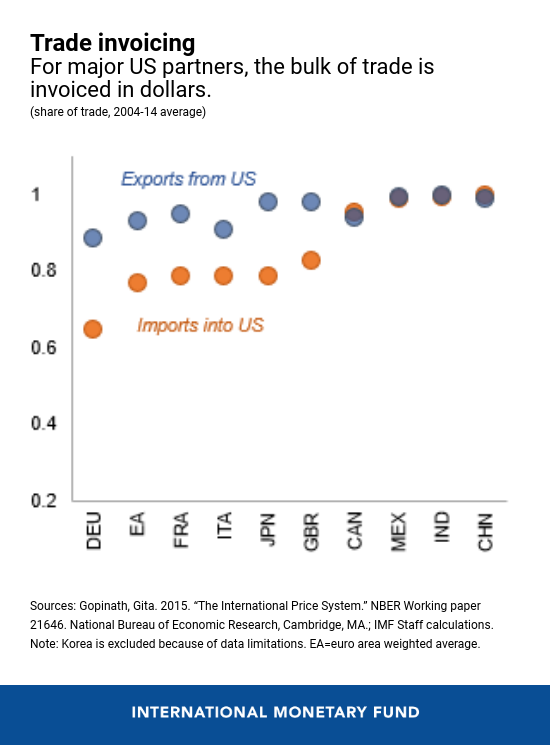

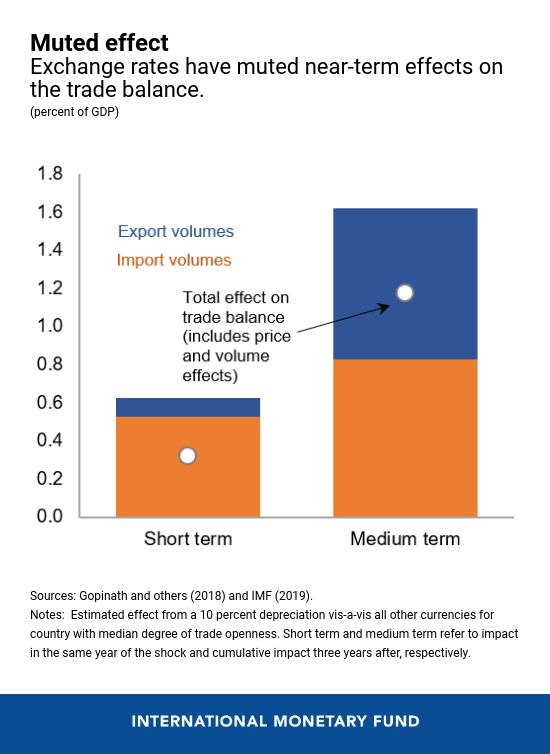

As we estimated in our 2019 External Sector Report , the expenditure switching effects of a currency weakening are generally small, especially within a 12-month period. A 10 percent depreciation (vis-à-vis all currencies) improves a country’s trade balance by about 0.3 percent of GDP in the near term, on average, with most of the effects coming through a contraction of imports. In part, this reflects the fact that trade is largely invoiced in dollars, which means that for most countries export volumes tend to respond little to exchange rates in the short run. This applies to key US trading partners, where the bulk of exports to and from the United States are invoiced in dollars. It is worth noting that in the case of the United States, the muted impact on the trade balance reflects a weak response of imports.

To be sure, the adjustment becomes more balanced over time as exports respond more meaningfully to exchange rate movements, although the full expenditure switching effect remains relatively modest: a 10 percent depreciation leads, on average, to a 1.2 percent of GDP improvement in the trade balance over a span of three years. So, while exchange rates facilitate durable external adjustment, the expenditure switching effect of a currency weakening, or its negative impact on trading partners, should not be overplayed.

Counterproductive policy options

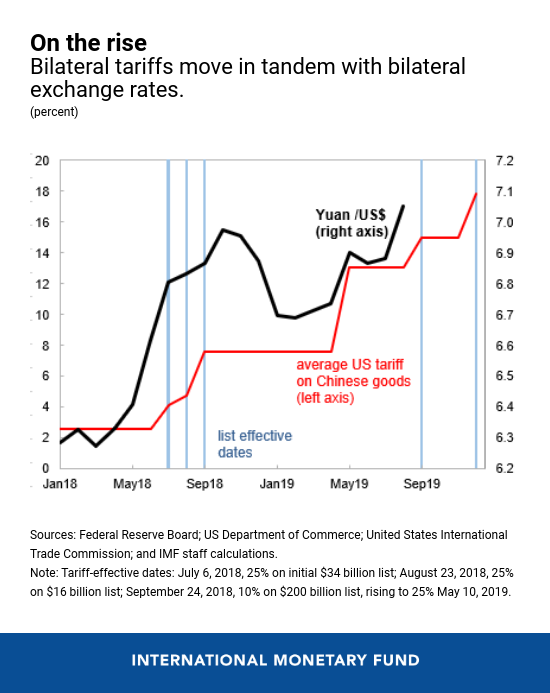

To tackle currency overvaluation concerns, policymakers are considering several measures. Some involve imposing tariffs on imports from countries deemed to have undervalued currencies. Can they make a difference? One key aspect is worth keeping in mind: tariffs and exchange rates work differently. A 10 percent tariff does not necessarily offset a 10 percent more appreciated (overvalued) exchange rate. Take for example the trade dispute between the United States and China. Since early 2018, the average US tariff on goods imported from China has increased by about 10 percentage points, and it would increase by another 5 percentage points if recently announced plans to impose additional levies are carried out. Meanwhile, the renminbi has depreciated by about 10 percent relative to the dollar, largely as a result of these trade actions and associated uncertainties—the increased flexibility of the renminbi has allowed it to be a buffer against trade shocks.

One might think that the impact of higher tariffs on imports from China would be offset by the stronger dollar, because as the US currency strengthens Chinese goods should become cheaper. But in reality, as discussed in an earlier blog , US importers and consumers are bearing the burden of the tariffs. The reason: the stronger US currency has had a minimal impact thus far on the dollar prices Chinese exporters receive because of dollar invoicing.

Moreover, higher bilateral tariffs are unlikely to reduce aggregate trade imbalances, as they mainly divert trade to other countries. Instead, they are likely to harm both domestic and global growth by sapping business confidence and investment and disrupting global supply chains, while raising costs for producers and consumers.

Another kind of policy proposal aims to weaken a country’s own currency directly by buying foreign currencies or taxing inflows of capital to offset policies adopted by other countries. These proposals are cumbersome to implement and likely to be ineffective, given the depth of markets for reserve currencies such as the dollar and euro. What is more, they have negative implications for the orderly working of the international monetary system.

Policies of either kind will likely encourage retaliation, undoing any benefit for a single country and simultaneously making all nations worse off, while also possibly violating international obligations such as those to the World Trade Organization.

Constructive, shared solutions

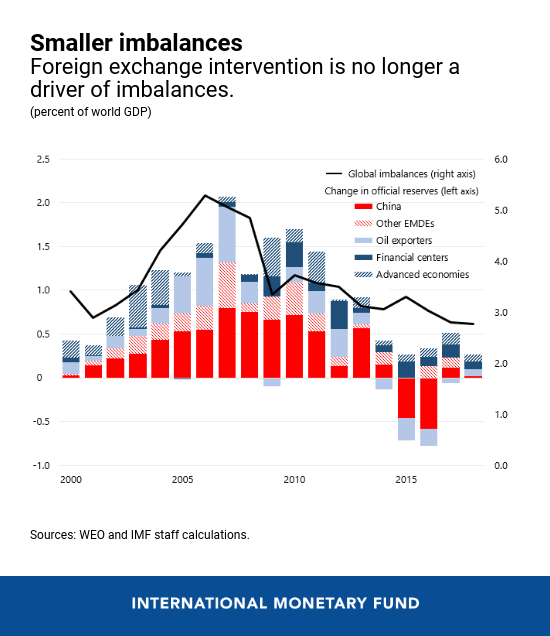

It should be stressed that external positions are not grossly misaligned, and policies to weaken currencies by intervening in foreign exchange markets are much less common today than in the past. External imbalances are down sharply from the peaks seen during the global financial crisis, and the dollar was only moderately overvalued in 2018. This is in sharp contrast to the mid-1980s, when under the Plaza Accord major central banks acted in concert to address a large dollar overvaluation.

While external positions do not present an imminent danger to global stability, actions of the right type are needed to sustain the progress made in reducing imbalances over the last decade and also to strengthen global growth. Both deficit and surplus countries should tackle the underlying macroeconomic and structural sources of imbalances rather than adopt ineffective, or even counterproductive, measures such as tariffs.

Deficit countries, like the United States and the United Kingdom, should reduce budget deficits without sacrificing growth and strengthen the competitiveness of their export industries; options include investing more in skills of workers and encouraging old-age saving. Surplus countries, like Germany and Korea, should use fiscal policy where possible to invest more in infrastructure and adopt reforms that encourage private investment. Such reforms may include supporting innovation through tax incentives for research and development and lowering barriers to entry in business services and regulated professions.

China, whose external position was broadly in line with fundamentals in 2018, also has a role to play. In particular, further structural reforms are needed to ensure a lasting external rebalancing, as it gradually addresses vulnerabilities from the high levels of private and public debt (see the 2019 Article IV consultation for China ). Steps include reforming state-owned enterprises, enhancing the social safety net, opening up more sectors to private and foreign competition, and removing impediments to trade.

Finally, both surplus and deficit countries must recognize that they share the responsibility to secure a stronger and more balanced global economy. That means finding durable solutions to trade disputes to address concerns about export subsidies and weak intellectual property protection, while also modernizing the international trade system in areas such as services and e-commerce. There are serious problems to contend with, such as rising inequality and sluggish growth. Currencies are neither the hammer nor the nail.