As we approach the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the former socialist countries of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe (CESEE) have made tremendous progress in becoming full-fledged market economies and raising income levels. Large-scale privatization in the 1990s was a key element of this transition but produced mixed results. In some cases, privatization generated broad-based ownership and healthy competition, while in some other countries, privatization did not advance so far, or led to public monopolies being replaced by private ones. This experience has highlighted the importance of a strong institutional and competitive environment, including better governance of both public and private entities.

State owned enterprises systematically underperform relative to private sector counterparts in nearly all countries.

Although the state’s role in the economy has diminished dramatically in the region, state ownership still remains significant in many countries and sectors. In the context of slower growth and convergence since the global financial crisis, there is now growing interest in whether an enhanced role for state-owned enterprises and banks (SOEs and SOBs) could be an important source of growth, or whether they would just impose a further drag on the economy.

Assessing state ownership

In this context, in a new study, prepared in collaboration with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the IMF examines the current footprint of state-owned enterprises and state-owned banks in the region, how they are performing, and what policies could be pursued to improve their management and efficiency. To answer these questions, our paper draws on original surveys, company and bank level databases, and case studies.

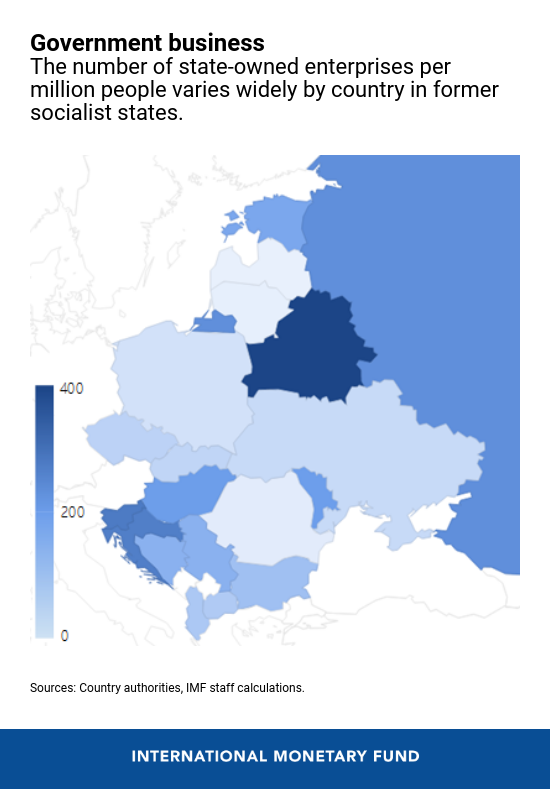

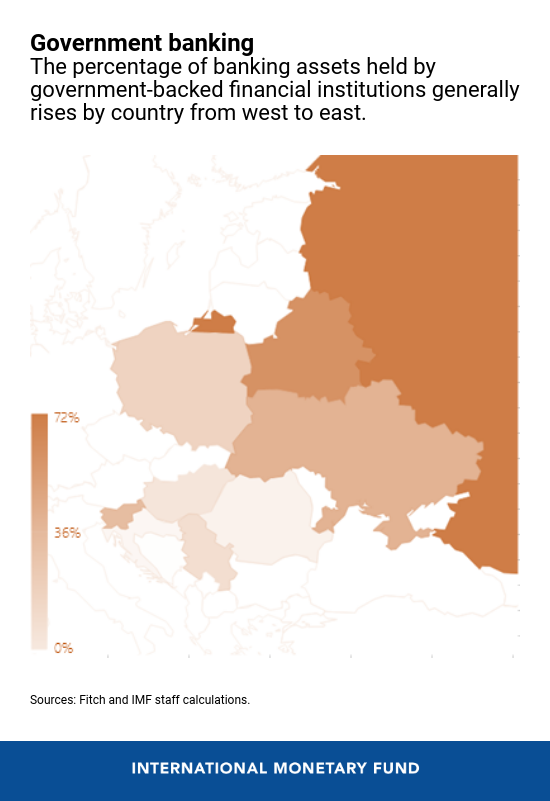

State companies now account for between 2 percent and 15 percent of total employment in the CESEE countries, except for Belarus where they still make up one-third of the economy. They are especially prevalent in sectors such as mining, energy, and transport. In the financial sector, the variation is even greater: in more than half the countries, state-owned commercial banks are small or non-existent, while in others such as Russia they are large or even dominant.

Systematic underperformance

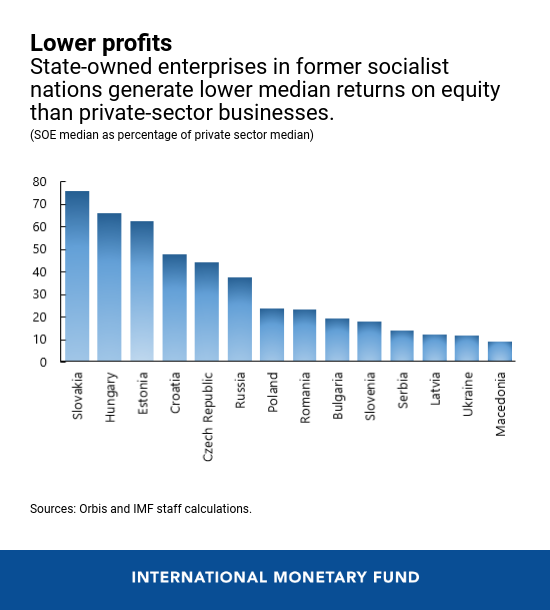

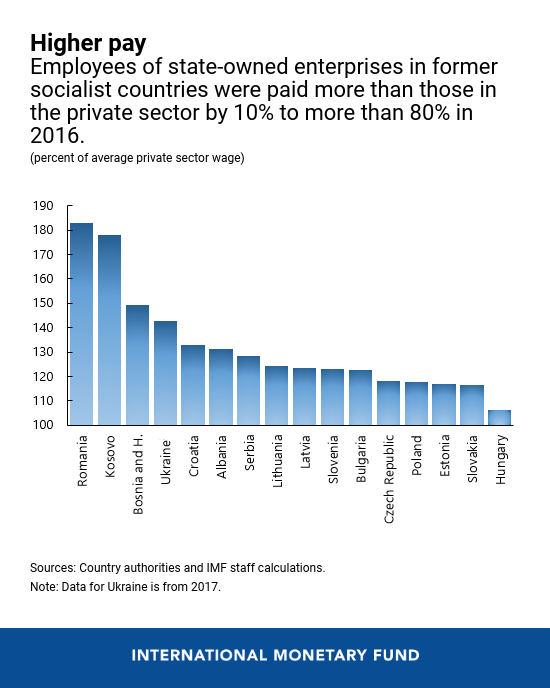

Our analysis finds that state-owned enterprises systematically underperform relative to private sector counterparts in nearly all countries. They tend to hoard labor, pay more generously, and generate less revenue per employee than private sector peers.

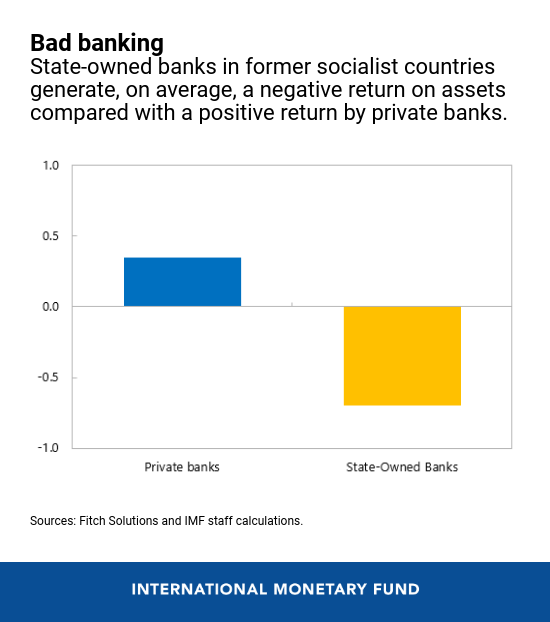

Unsurprisingly, they turn out to be less productive and less profitable. Potentially large output gains would be achieved if productivity of state-owned enterprises could be raised to private sector levels. A similar picture emerges for state-owned banks, which in most countries make less-sound lending decisions than private counterparts and have lower profitability, often associated with higher shares of problem loans.

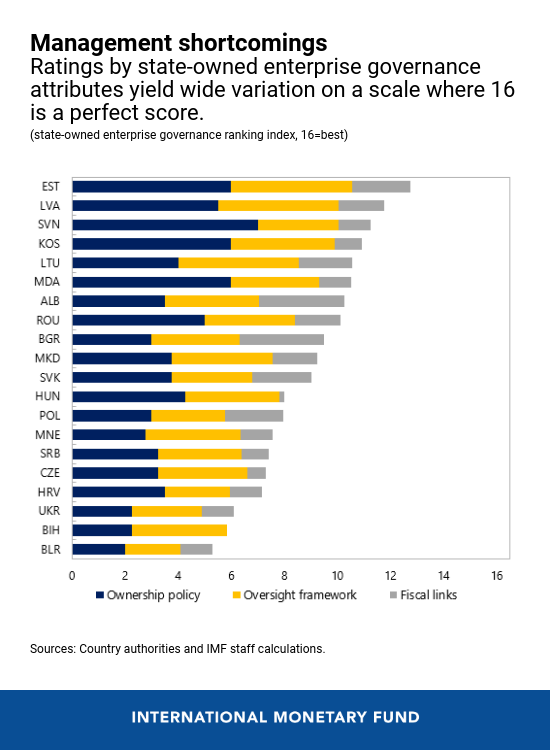

While our survey finds that some state-owned entities have dual commercial and noncommercial mandates, the analysis finds little evidence that the inefficiencies arising from state ownership can be justified by noneconomic objectives. The study does, however, point to significant shortcomings in governance and oversight of state companies, though with significant variation across countries.

Policy conclusions

The study points to some important policy conclusions.

First, countries should take a fresh look at the rationale for existing state ownership, taking into account the costs, benefits, and risks of state ownership, whether state-owned enterprises have clearly articulated objectives, and whether there are more-efficient means to achieve any noncommercial policy objectives. Countries can employ a triage approach to identify viable state entities, those that are viable but need restructuring, and nonviable enterprises. Privatization (or bankruptcy) will sometimes be appropriate choices but are not realistic options in some cases.

Second, it is vital to address shortcomings in governance. Many countries need to strengthen their government ownership policy, including centralized and depoliticized management of state shareholdings, selection of competent management and supervisory board members, and establishing supporting legal and regulatory frameworks. State-owned entities should be subject to periodic assessments of performance and accountability against clearly articulated objectives, and relative to private sector comparators. And although improving governance is paramount, hard choices such as shedding employment or divesting noncore assets will often need to be part of the solution.

The diversity of experience across the region suggests countries can learn a lot from each other about how to better prioritize and manage state-owned enterprises and SOBs. A regional coordination initiative could be a good way to support these efforts. At a time when growth-enhancing policies can be hard to identify, improving the performance of existing state-owned entities, or exiting in favor of the private sector where appropriate, could provide much-needed support for the economy.