The long road towards development

The world has achieved a tremendous amount in the past five decades on the development front. Since 1990 alone, over a billion people have lifted themselves out of extreme poverty. Never before in human history have we witnessed progress on this scale. It reflects a combination of important economic reforms that led to robust economic growth in most of the developing world and the concerted efforts of the international community to support countries in achieving the Millennium Development Goals, agreed in 2000.

Let’s look at two Indonesian women: Sri, the grandmother, and Tuti, her granddaughter. Sri’s annual income was US$1,500. If she had not died during childbirth, then she surely would have lost one of her seven children before the age of one. Tuti, on the other hand, has an annual income of US$11,200 and is hardly at risk of either dying during childbirth or of losing a child.

Indonesia continues to progress along its development path. The Indonesian government is forging ahead with plans to fund development needs in education, health, and infrastructure, to be financed by increasing tax revenues. Boosting revenues by an additional five percentage points of GDP over five years would ensure that Indonesia is on track to meet the SDGs by 2030.

Yet other countries lag behind. In too many parts of the world, poverty remains a fundamental barrier to economic advancement. Take Benin, for example. A girl born in Benin today has the same life expectancy as an Indonesian woman born 40 years ago. Benin has about the same income per capita as Indonesia did at that time. Even if Benin were to replicate Indonesia’s fast progress, it would be 2050 before Benin’s girls would reach the development standards available to Indonesian girls in 2030.

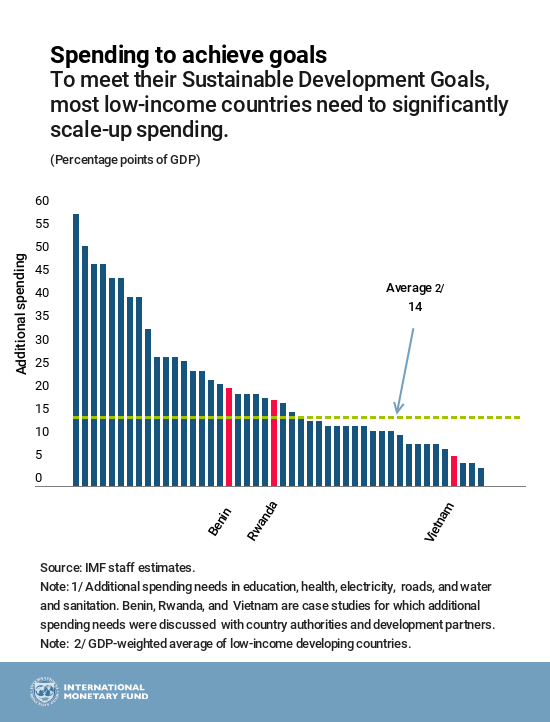

Low-income countries need to increase spending in education, health, water and sanitation, roads, and electricity.

The big challenge

This is not good enough. The SDGs are about making sure that all children, wherever they are born, are given a fair chance by 2030.

The IMF has done some analytical work to see what it would take for low-income developing countries such as Benin to meet the SDGs. We looked at five areas that are critical for sustainable and inclusive growth: education, health, water and sanitation, roads, and electricity.

How much more spending in these areas is needed to put countries on track to meet the SDGs? We estimate that low-income developing countries need additional annual outlays of 14 percentage points of GDP on average. Across 49 low-income developing countries, additional spending needs amount to about US$520 billion a year—an estimate that is in the same ballpark as that of other institutions. Clearly, significant new spending is needed.

Addressing SDG spending needs

So how can we tackle this immense challenge—one that is essential to the well-being of whole generations?

We all need to make a concerted effort, most importantly individual countries, but also international organizations, official donors and philanthropists, the private sector, and civil society.

As a necessary first step, low-income developing countries must own the responsibility for achieving the SDGs. Country efforts should focus on strengthening macroeconomic management, enhancing tax capacity, tackling spending inefficiencies, addressing the corruption that undermines inclusive growth, and fostering business environments where the private sector can thrive. Action in these areas will support the growth that is fundamental to SDG progress—and the IMF will work closely with its member countries to actively support this reform agenda.

Secondly, countries have substantial scope to raise tax revenues. An ambitious but reasonable target for many countries is to increase their tax ratio by 5 percentage points of GDP; this will require strong administrative and policy reforms, where the IMF and other development partners can play a key supporting role.

Boosting tax revenues by this amount may be sufficient to put achievement of the SDGs in reach for emerging market economies such as Indonesia, but it will not be sufficient to meet the financing needs of most low-income developing countries, including Benin.

For low income countries, in addition to using existing resources better, financial support will be needed from bilateral donors, international financial institutions, and philanthropists—and from private investors. These investors can make an important contribution in sectors such as infrastructure and clean energy if the required reforms are put in place to improve the business climate. Encouraging private investment that supports national development is precisely the goal of initiatives such as the Compact with Africa.

Extra financing can also be obtained from international financial markets and lenders. In general, borrowing on commercial terms is a double-edged sword if funding is not used for high-return projects. As the IMF has emphasized in recent years, debt burdens are rising: forty percent of low-income developing countries are now assessed by the IMF and World Bank to be at high risk of debt distress or in debt distress—debt distress that would significantly disrupt the economic activity and employment growth on which progress towards the SDGs depends.

Foreign aid, preferably in the form of grants, remains crucial in supporting the development efforts of poorer countries. Advanced economies can do more, including by moving towards 0.7 percent of gross national income in aid—and can also better target their aid budgets to support countries most in need of such assistance. Budget conditions are tight in many advanced economies, but the economic returns on well-targeted aid—in terms of poverty reduction, job creation, and improving security and stability—are very high.

Beyond spending

Yet the challenges go beyond ramping up development outlays.

The example of Indonesia shows that development and economic growth reinforce each other. An important aspect of the broader challenge is the environment in which countries seek to generate and sustain stable growth. This requires a variety of global public goods including geo-political stability, open trade, and climate initiatives, as well as good governance, which depends on tackling both the supply and demand elements of corruption. These important foundations for development underscore the need for joint action by all stakeholders for the SDGs to be realized.

Kofi Annan, whose recent death we still mourn, once said: “We have the means and the capacity to deal with our problems, if only we can find the political will.” This is true for the entire SDG agenda. Let us summon that political will to give all of our children a chance.