July 24, 2017

Versions in عربي (Arabic), Bahasa (Indonesian), 中文 (Chinese), Français (French), 日本語 (Japanese), Русский (Russian), and Español (Spanish)

[caption id="attachment_20732" align="alignnone" width="1024"] (photo: IMF)[/caption]

(photo: IMF)[/caption]

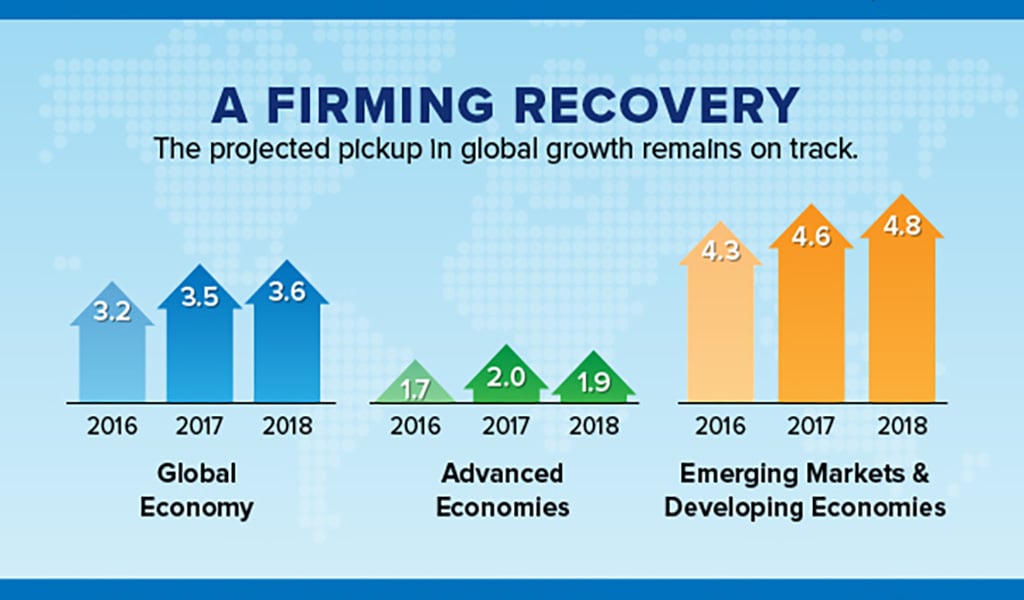

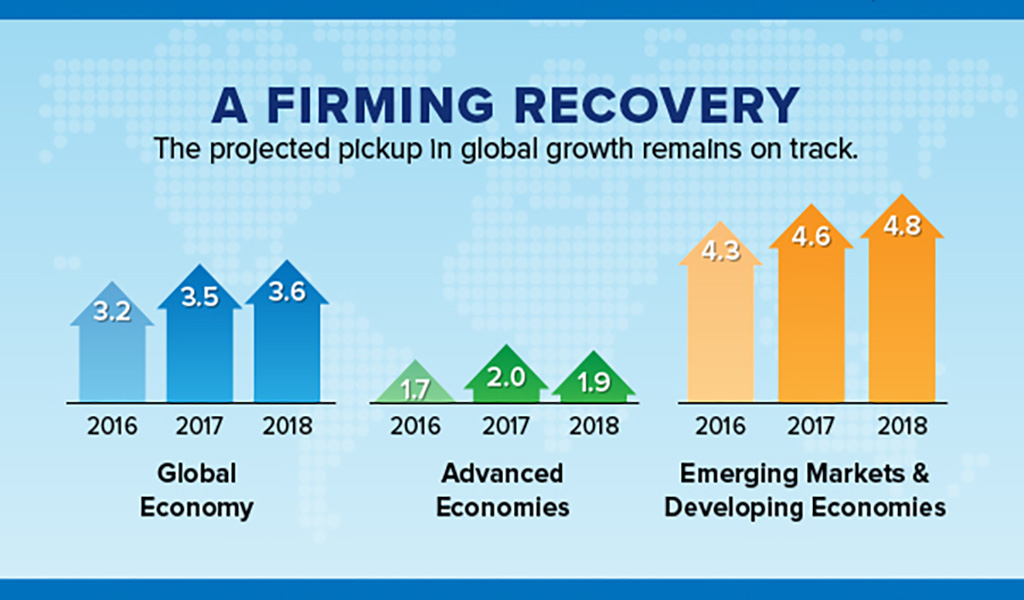

The recovery in global growth that we projected in April is on a firmer footing; there is now no question mark over the world economy’s gain in momentum.

As in our April forecast, the World Economic Outlook Update projects 3.5 percent growth in global output for this year and 3.6 percent for next.

The distribution of this growth around the world has changed, however: compared with last April’s projection, some economies are up but others are down, offsetting those improvements.

Notable compared with the not-too-distant past is the performance of the euro area, where we have raised our forecast. But we are also raising our projections for Japan, for China, and for emerging and developing Asia more generally. We also see notable improvements in emerging and developing Europe and Mexico.

Where are the offsets to this positive news on growth? From a global growth perspective, the most important downgrade is the United States. Over the next two years, U.S. growth should remain above its longer-run potential growth rate. But we have reduced our forecasts for both 2017 and 2018 to 2.1 percent because near-term U.S. fiscal policy looks less likely to be expansionary than we believed in April. This pace is still well above the lacklustre 2016 U.S. outcome of 1.6 percent growth. Our projection for the United Kingdom this year is also lowered, based on the economy’s tepid performance so far. The ultimate impact of Brexit on the United Kingdom remains unclear.

Overall, though, recent data point to the broadest synchronized upswing the world economy has experienced in the last decade. World trade growth has also picked up, with volumes projected to grow faster than global output in the next two years.

There do remain areas of weakness, however, among middle- and low-income countries, notably commodity exporters who continue to adjust to reduced terms of trade. Latin America still struggles with sub-par growth, and we have lowered projections for the region over the next two years. Growth this year in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to be higher than last year, but remains barely above the population growth rate, implying stagnating per capita incomes.

Risks

There are risks that the outcome could be better or worse than we now project. Near term, there is the possibility of even stronger growth in continental Europe, as political risks have diminished.

On the downside, however, many emerging and developing economies have been receiving capital inflows at favorable borrowing rates, possibly leading to risks of balance of payments reversals later. Strains could emerge if advanced economy central banks show an increasing preference for monetary tightening, as some have in recent months. Core inflation pressures remain low in advanced economies and measures of longer-term inflation expectations show no indications of upward drift beyond targets, so central banks should proceed cautiously based on incoming economic data, reducing the risk of a premature tightening in financial conditions.

Supportive policy has promoted China’s recent high growth rates, and we have upgraded our 2017 and 2018 forecasts for China, by 0.1 and 0.2 percentage point, respectively, to 6.7 and 6.4 percent. But higher growth is coming at the cost of continuing rapid credit expansion and the resulting financial stability risks. China’s recent moves to address nonperforming loans and to coordinate financial oversight therefore are welcome.

Finally, the threat of protectionist actions and responses remains salient in the near and medium terms, as do geopolitical risks.

The longer horizon

Despite the current improved outlook, longer-term growth forecasts remain subdued compared with historical levels, and tepid longer-term growth also carries risks.

In advanced economies, median real incomes have stagnated and inequality has risen over several decades. Even as unemployment is falling, wage growth still remains weak. Thus, continuing slow growth not only holds back the improvement of living standards, but also carries risks of exacerbating social tensions that have already pushed some electorates in the direction of more inward-looking economic policies. In emerging economies in contrast, despite generally higher inequality than in advanced economies, substantial income gains have accrued even to those low in the income distribution.

The current cyclical upswing offers policymakers an ideal opportunity to tackle some of the longer-term forces behind slower underlying growth. Suitable structural reforms can raise potential output in all countries, especially if supported by growth-friendly fiscal policies including productive infrastructure investment, provided there is room in the government budget. In addition, investment in people is critical—whether in basic education, job training, or reskilling programs. Such initiatives will both increase labor markets’ resilience to economic transformation and raise potential output. The same policy measures that can help economies adjust to globalization—as described in the recent report we co-authored with the World Bank and World Trade Organization—are more broadly necessary to meet the challenges of technology and automation.

Strengthening multilateral cooperation is another key to prosperity, in a range of areas including trade, financial stability policy, corporate taxation, climate, health, and famine relief. Where domestic developments have a strong international impact, policies based narrowly on national advantage are at best inefficient and at worst highly damaging to all.