A country with the opposite imbalance—a current account surplus—is accumulating claims on the rest of the world. Because all borrowing must be matched by lending, the sum of all the world’s current account deficits is equal the sum of its surpluses—a principle known as multilateral consistency.

Imbalances can be healthy…

In many cases, current account imbalances can be entirely appropriate, even necessary. For example, countries whose populations are aging rapidly—such as many advanced economies in Europe and Asia—need to accumulate funds that they can draw down when their workers retire. If domestic investment opportunities are few, it makes sense for these countries to invest abroad instead. The result will be a current account surplus.

In other countries, the opposite is true. Young and rapidly growing economies with ample investment opportunities benefit from foreign funding, and can afford to accumulate debts (by running current account deficits), provided they can repay them out of future income.

… or signal risks

Sometimes, however, external imbalances can point to macroeconomic and financial stress—both for individual countries and for the world economy, as earlier work by IMF colleagues and myself has explained. Just as over-indebted households can lose access to credit, economies that accumulate external liabilities on too large a scale may become vulnerable to sudden stops in capital flows that force abrupt cuts in spending–making financial crises more likely.

At the same time, persistent imbalances may be a symptom of distortions in the domestic economy that can harm growth—for example, insufficient social safety nets that provoke excessive precautionary saving. Removing distortions and reducing imbalances is then in the interest of the country itself. Reducing imbalances may also benefit the global community, making it less vulnerable to contagion from financial crises or to the downsides of excessive surpluses. These downsides could include depressed global demand and increased protectionist sentiment in deficit countries.

Learning from history

History offers many examples of disruptions related to large external imbalances. The most infamous is arguably the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s. It was preceded by a failure of international cooperation to address persistent imbalances between countries with large surpluses (notably the United States and France) and deficits (including Germany and the United Kingdom). The resulting breakdown of the global economic order inspired the establishment of the IMF after World War II, with its mandate to promote international monetary cooperation and help countries build and maintain strong economies.

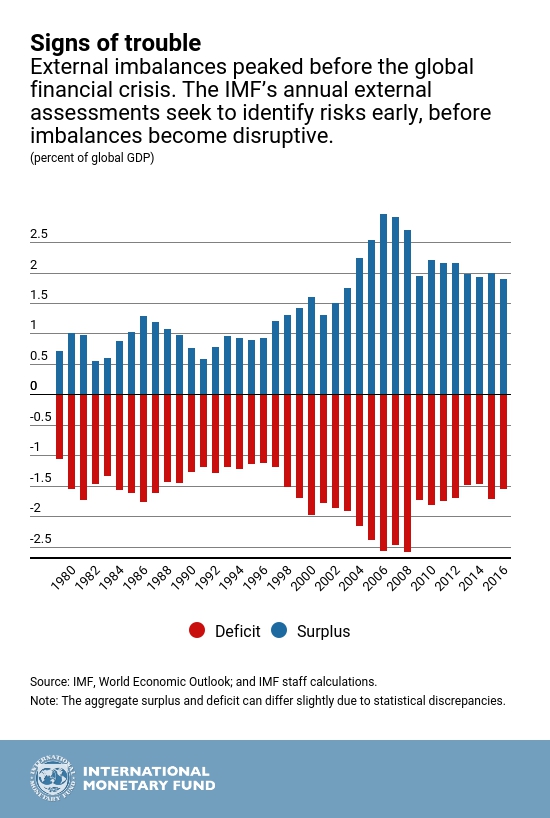

More recently, the global financial crisis was preceded by record imbalances and a simultaneous but neglected buildup of vulnerabilities. The imbalances unwound only in a once-in-a-generation recession that caused economic distress around the globe.

Assessing external imbalances

Given its mandate, what can the IMF do to reduce the risk of disruptive current account imbalances? Taking to heart one lesson of the global financial crisis, since 2012, we conduct systematic, annual assessments for the world’s 28 largest economies and for the euro area. Together these economies account for more than 85 percent of world GDP.

The objective is to identify risky developments early, and to offer policy advice for countries on how to address potentially disruptive imbalances. Results are featured in both the annual Article IV consultation reports for each member country, and in a comprehensive External Sector Report published once a year. The exercise is multilateral in nature—hence it focuses on a country’s transactions with the entire rest of the world, not on countries’ bilateral balances. This focus is crucial to uncover the macroeconomic factors that drive global imbalances.

Because some imbalances are justifiable, the key challenge is to determine how much of an external surplus (or deficit) is appropriate—and how much is too much, or “excessive.” Because the drivers of current account balances are so very complex, no simple approach to identifying excessive imbalances is likely to give the right answer for every country. That’s why the IMF has developed a detailed evaluation methodology that, while not perfect, in our view strikes a good balance of economic theory, statistical estimation, and country-specific knowledge in evaluating potential risks.

The nuts and bolts

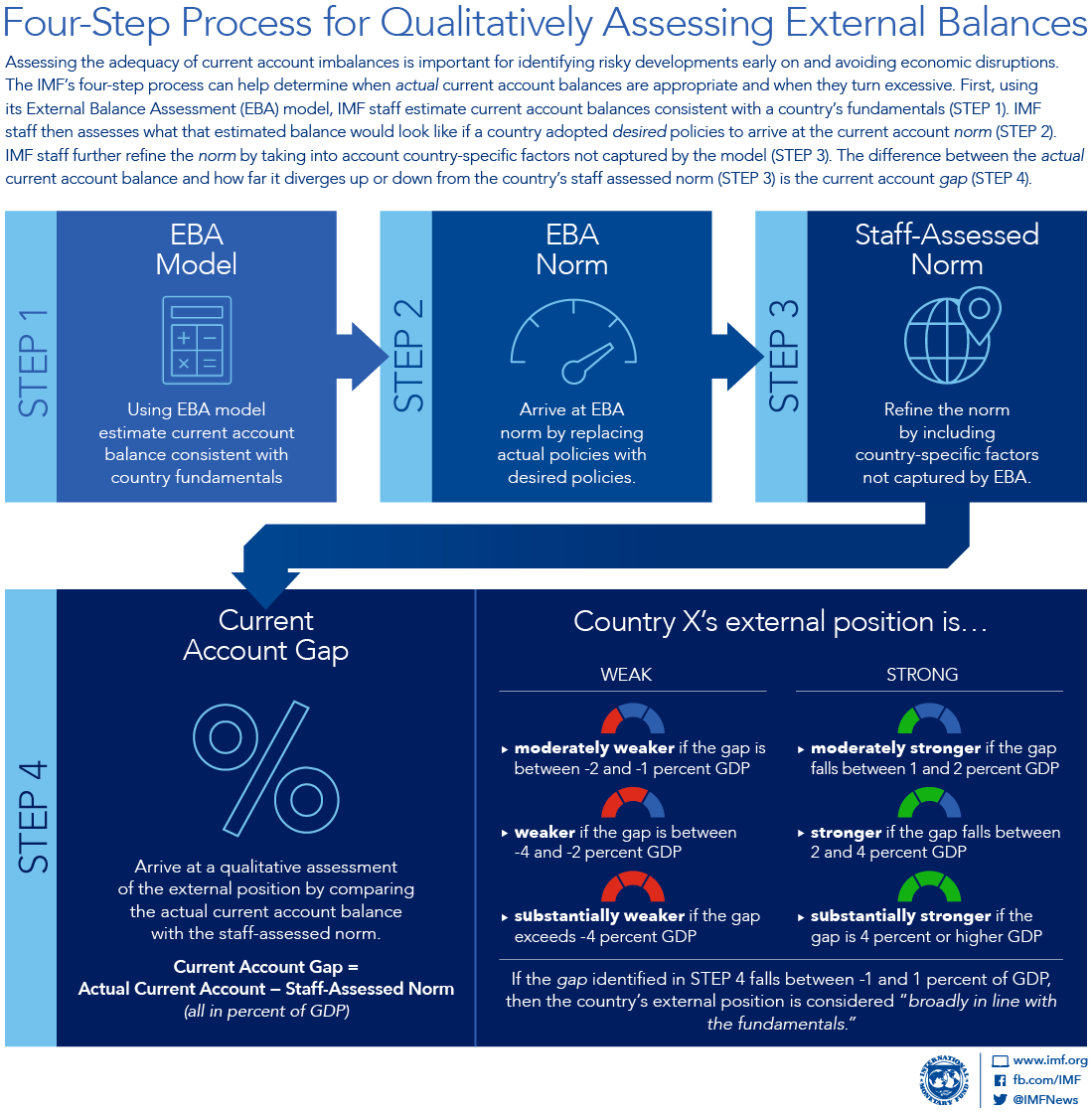

Conceptually, our external assessments compare an economy’s actual current account balance with a current account norm. We follow four steps:

Step 1: Projected current account. The starting point is the External Balance Assessment (EBA) model. The model estimates the “average” current account balance of an economy with certain characteristics—say, demographic structure or income level—and economic policies—say, the fiscal stance. As complementary information and a control check, we also run similar models for the real effective exchange rate to derive a benchmark for assessments of under- or overvaluation.

Step 2: EBA norm. “Average” does not necessarily mean “optimal” or “desired.” For example, if a country runs an inadequate fiscal policy—either too lose or too tight—we compute the current account balance that would prevail if fiscal policy were appropriate. Replacing actual policies with desired policies in the EBA model gives us a current account norm.

Step 3: Staff-assessed norm. No model is perfect. Thus, it is not unusual to adjust the model estimates for omitted country-specific factors, which are based on insights our country teams gain in the consultation process. Take the example of a young, rapidly developing economy. The model may indicate a large current account deficit as appropriate—larger than the economy can typically finance. In this case, we adjust the estimated current account norm upward (that is, toward a lower deficit). We go to great lengths to ensure that such adjustments are as accurate and impartial as possible, and that they are multilaterally consistent–which means that they add up globally.

Step 4: Current account gap. The difference between the actual current account balance and the staff-assessed norm is the “current account gap”—the basis for our assessments. Conceptually, the gap captures everything that drives an economy’s external balance away from its appropriate level—from inadequate macroeconomic policies to domestic distortions. These gaps are then translated into qualitative assessments—the broad categories of which are sketched in Figure 2—to inform a discussion around the policies that are best suited to close them.

Evolving external assessments

It is important to keep in mind that both norms and current account balances do evolve. External assessments are a snapshot at a certain point in time, not a fundamental judgment about the economy’s immutable nature.

Further, and despite our best efforts, room for some error remains. That’s why we put confidence bands around our assessments. But even then, it is possible to miss relevant factors. As always, a degree of humility therefore is necessary: while we conduct external assessments in the best way we know, this does not mean they are perfect—so we work continually to upgrade and refine our EBA model and analysis.

A global public good

In the end, the IMF’s assessments are an analytical tool—no more, but also no less—to determine the difficult and often contentious question of when external imbalances are appropriate or when they signal risks. As such, they provide an important public good by alerting the global community to potential balance of payments stresses that countries need to address together. To be effective, our analysis and recommendations need to find open ears and minds among policymakers, along with the will to act.

Combating excess global imbalances is a joint responsibility. No single country can do it effectively on its own. All countries must act cooperatively in order that all gain. Otherwise, we leave ourselves open to the types of crises that have derailed global stability in the past.