Versions in عربي (Arabic), 中文 (Chinese), Français (French), 日本語 (Japanese), Русский (Russian), and Español (Spanish)

It is quite likely you are reading this on a smartphone or tablet assembled in an emerging market economy. The beverage beside you could well be tea grown in Sri Lanka or Kenya. And there is a chance that you are —or soon will be—on a plane headed for Shanghai, Sao Paulo, or St. Petersburg.

The list could go on. But even from a few examples around us, it is easy to detect the pervasive role of emerging market and developing economies in the global economy these days—a role that has grown more important over time.

Improved policy frameworks and structural reforms in emerging market and developing economies over the past twenty years have been crucial for this transformation. But as our research in Chapter 2 of the April 2017 World Economic Outlook shows, the external environment has also played its part in facilitating their rise.

These economies now face a possibly more complicated external environment than they have grown accustomed to in recent decades. Nevertheless, they can still enhance the growth impulse from less supportive external conditions with the right policy mix and by continuing to strengthen their institutional frameworks.

Role of external conditions

Emerging market and developing economies now account for close to 80 percent of global economic growth, almost double their share from two decades ago. Their relevance for the global economy isn’t simply as centers of production or trading hubs packaging and shipping goods to advanced economies. They have also become increasingly important as final destinations for consumer goods and services, now accounting for close to 85 percent of the growth in global consumption, more than double their share in the 1990s.

These economies have become more integrated into the global trading system and international capital markets since the 1990s. And as this process has unfolded, the relative prices of their exports and imports, external demand, and, in particular, external financial conditions, have increasingly influenced their growth in real income per capita.

Our study finds, for instance, that about one third of the 1½ percentage points pickup in the average growth rate of income per capita since 2005, relative to the 1995-2004 period, can be attributed to stronger capital inflows. Over time, demand for exports from other emerging market and developing economies has also exerted a more powerful force on these economies’ medium-term growth.

Beyond the numbers, the influence of the external environment has extended to the nature of their growth process. Several of these economies have experienced episodes of growth accelerations and reversals with sustained changes in growth rates. These episodes appear to have a long-lasting effect on the level of income per capita. The chapter finds that favorable external conditions increase the likelihood of growth accelerations and lower that of reversals.

Growth in a more complicated external environment

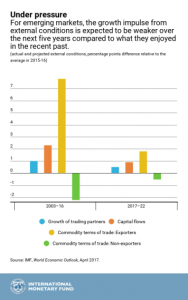

Emerging market and developing economies enjoyed exceptionally favorable external conditions over long stretches of the post-2000 period—strong external demand, relatively abundant capital inflows, and an upswing in commodity prices.

Over the past few years, however, the external environment has become more complicated for these economies. The slow recovery from the crisis in advanced economies has weakened demand for emerging market and developing economy exports. China has relied less on commodity imports as it rebalances its economy toward consumption and services. And the commodity cycle, more broadly, has turned since 2014, reducing growth rates among commodity exporters.

Some of these shifts in the external environment may persist. Additional elements in the mix are a risk of protectionism in advanced economies, and a general tightening of external financial conditions as US monetary policy normalizes. Emerging market and developing economies are therefore likely to experience a weaker growth impulse from external conditions than in the past.

Room for convergence

Despite this more complicated environment, the chapter’s analysis finds that these economies can still get the most out of a weaker growth impulse from external conditions by strengthening their institutional frameworks, protecting trade integration, permitting exchange rate flexibility, and containing vulnerabilities from high current account deficits and large public debts.

Some of these policies can also directly help boost growth in emerging market and developing economies, regardless of the shift in external conditions. After all, with 90 percent of the group at levels of income per capita less than half that in the United States, there is still considerable room for catch-up growth and convergence.