Versions in: عربي (Arabic), 中文 (Chinese), Français (French), and Español (Spanish)

Low-income countries should build more infrastructure to strengthen growth. A new IMF analysis looks at ways to overcome obstacles.

The clock is now ticking on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and while investment—critical to this agenda—has been rising in recent years among low-income countries, weak infrastructure is still hampering growth. Governments need to make significant improvements to lay foundations for flourishing economies: roads to connect people to markets, electricity to keep factories running, sanitation to stave off disease, and pipelines to deliver safe water.

For that reason, upgrading and expanding transport, telecommunications and utilities is a key pillar in many countries’ national development strategies.

What are the challenges, and what needs to be done to achieve the goals in low-income states? A chapter in a recent report by the IMF delves into these questions.

High debt, insufficient resources and capacity constraints

In many low-income countries, public debt levels have risen and external financing conditions have tightened, which has made taking out loans to invest in infrastructure projects increasingly difficult and risky. During 2015 alone, the ratio of public debt to GDP rose from 34 to 42 percent.

A survey reveals that the availability of external financing and administrative capacity constraints are key obstacles to scaling up public infrastructure investment in the most vulnerable countries. However, for low-income countries better connected to global capital markets, it is the sufficiency of domestic financial resources that is the most important concern.

Bridging the gap on multiple fronts

Given their limited resources, poorer countries can benefit substantially from improving the efficiency of their public investment. As documented in the IMF’s recent analysis, value for money in public investment varies considerably among low-income countries, and is generally lower than in other states. While the broad principles for improving public investment efficiency—for example, that capital expenditure should go to most productive projects—are well understood, institutional mechanisms to achieve this (effective cost-benefit analysis; transparent procurement) are not always in place.

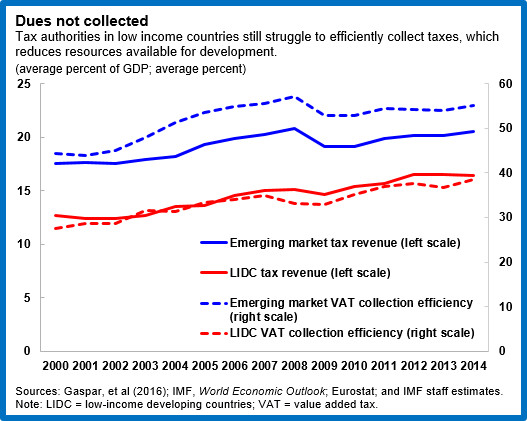

More domestic resources from taxes can create more space for priority spending areas such as infrastructure. However, despite some progress, tax revenues still remain lower in poorer countries than elsewhere, partly due to lower collection efficiency. Therefore, improving tax administration, broadening the tax base, closing unjustified loopholes, streamlining expenditures, and, in some cases, raising tax rates will help generate the budgetary resources to fund infrastructure provision.

Concessional financing will need to continue to play an important role in funding development in low-income countries. Increasing the capital of multilateral development banks and adjusting the way they deploy their capital could generate more resources for the poorest countries.

The rise of new bilateral donors, particularly China, and new institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, has brought additional funds for development.

That said, many potential donor countries are faced with their own fiscal challenges, limiting the prospects for a large increase in multilateral and bilateral donor financing. In any case, there is an overall agreement that even scaled up official development assistance is insufficient to meet the investment requirements of the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

Get the private sector involved

There is little purely private infrastructure in low-income countries outside the mobile telecommunications sector—but that notable exception demonstrates that the model is potentially viable. Small-scale applications in other sectors, such as solar micro-grids, reinforce this notion.

Alternatively, public and private capital can be combined in a public-private partnership, which is a relatively frequent model in electricity generation. Of course, a strong institutional framework and sound public-private partnership management are critical to avoid such structures unduly increasing fiscal risks.

How to attract private investment in infrastructure?

A favorable business environment, including stable macroeconomic conditions and predictable policies and regulations, tops the list. But it may not be sufficient. Numerous obstacles get in the way of connecting private investors to viable projects, even though large institutional pools of capital (close to $100 trillion in advanced economies) are looking for decent returns. In particular, there is limited expertise in low-income countries in structuring projects to ensure an acceptable risk-return combination for private investors.

Multilateral development banks help developing countries address many of these issues. Numerous project preparation facilities help structure viable projects—for example, the recently established Global Infrastructure Facility with an initial capitalization of $100 million.

In addition, development banks seek to catalyze private investment by providing risk mitigation through political risk insurance, credit guarantees, subordinated debt, and other instruments. This is a very promising direction, although progress has been limited so far.

The IMF has tools to help

The IMF assists its members interested in scaling up infrastructure investment. Its Infrastructure Policy Support Initiative is a suite of tools that help countries evaluate the macroeconomic and financial implications of alternative investment programs and financing strategies and bolster institutional capacity in managing public investment.

These tools have already been applied in a large number of countries, including Cambodia, Honduras, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Togo. The IMF also allocates one-fifth of its support for national capacity building to assistance in the areas of tax policy and administration, which are key to domestic revenue mobilization.