Versions in عربي (Arabic), 中文 (Chinese), Français (French), 日本語 (Japanese), Русский (Russian), and Español (Spanish)

Over the last six months, global financial stability risks increased as a result of the following developments:

- First, macroeconomic risks have risen, reflecting a weaker and more uncertain outlook for growth and inflation, and more subdued sentiment. These risks were highlighted yesterday at the World Economic Outlook press conference.

- Second, falling commodity prices and concerns about China’s economy have put pressure on emerging markets and advanced economy credit markets.

- Finally, confidence in policy traction has slipped, amid concerns about the ability of overburdened monetary policies to offset the impact of higher economic and political risks.

Earlier in the year, markets reacted negatively to these developments. Global equities plummeted; volatility rose sharply; talk of recession in advanced economies increased; and bank equity prices came under renewed pressure.

Today the situation in markets appears significantly better compared to the lows of mid-February. Equity markets have recovered much of their losses and oil prices are higher, while volatility has subsided. This improvement followed some better news on the economic front, as well as intensified policy actions by the European Central Bank, and a more cautious stance toward raising rates by the U.S. Federal Reserve. China has also stepped up efforts to strengthen its policy framework to bolster growth and stabilize the exchange rate.

A key question that this Global Financial Stability Report edition addresses is whether the turmoil that we have seen over the past months is now safely behind us, or is it a warning signal that more needs to be done? I believe it is the latter: more needs to be done to secure global stability.

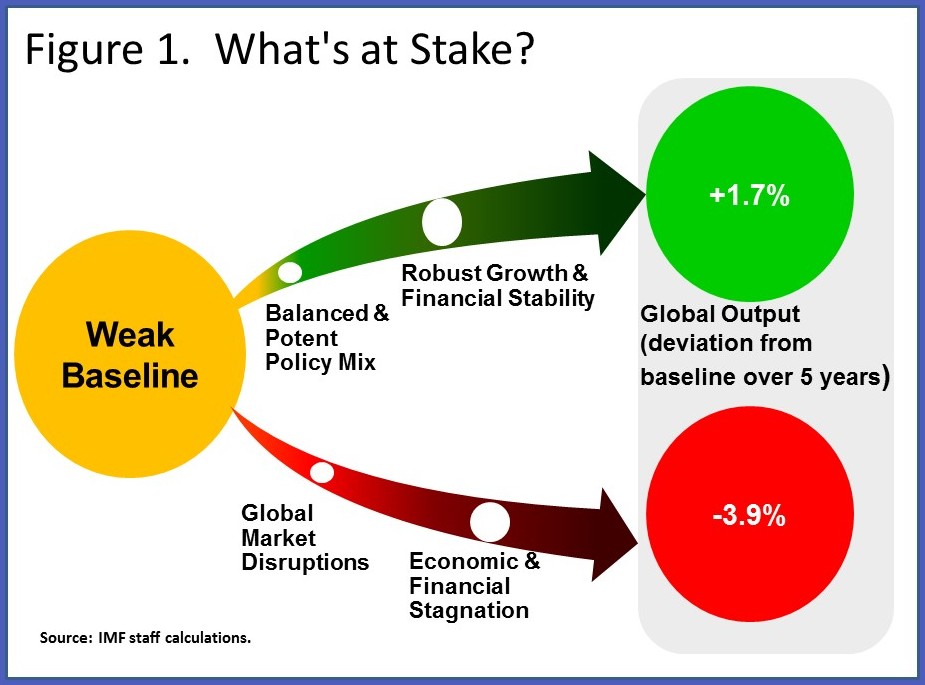

Much is at stake. Additional measures are needed to deliver a more balanced and potent policy mix. If not, market turmoil may recur and intensify, and could create a pernicious feedback loop of fragile confidence, weaker growth, tighter financial conditions, and rising debt burdens. This could tip the global economy into economic and financial stagnation. In such a scenario, we estimate that world output could fall by almost 4 percent, relative to our baseline projections, over the next five years (Figure 1). This would be roughly equivalent to forgoing one year of global growth.

So what needs to be done? We need to go beyond the status quo. We need a collective approach to policymaking to tackle a triad of global challenges. These are the same challenges that I underscored six months ago, namely crisis legacy issues still unaddressed in advanced economies, elevated vulnerabilities in emerging markets, and systemic market liquidity risks. The market turbulence we experienced earlier this year is a powerful reminder of this unfinished business.

Let me discuss now the challenges facing advanced economies and emerging markets, and what needs to be done to address them. Tackling these challenges will enable to expand world output by up to 1.7 percent, relative to the baseline, over the next five years (Figure 1). That is like securing an additional half a year of global growth.

The first challenge to tackle is crisis legacies in advanced economies, particularly banks, as they play a key role in financing the economy. Banks in advanced economies are now considerably safer. Yet they came under significant market pressures at the start of the year, as the economic outlook weakened and became more uncertain.

But banks also face important structural challenges in adapting to the new post-crisis realities that continue to depress their profitability. Many banks in advanced economies face significant business model challenges. We estimate that these banks account for about 15 percent of bank assets in advanced economies (Figure 2). In the euro area, market pressures also highlight long standing legacy issues. Elevated nonperforming loans urgently need to be tackled using a comprehensive strategy and excess bank capacity—namely, too many banks—will have to be addressed over time. Europe must also complete the banking union and establish a common deposit guarantee scheme.

The second key challenge to tackle is from emerging markets. The sharp fall in commodity prices has exacerbated both corporate and sovereign vulnerabilities, keeping economic and financial risks elevated. After years of growing indebtedness, emerging economies face a difficult combination of slower growth, tighter credit conditions, and volatile capital flows. So far, many economies have shown remarkable resilience to this difficult environment, thanks to the judicious use of buffers accumulated during the boom years. But buffers are depleting quickly, with some countries running out of room to maneuver.

As the health of the corporate sector deteriorates, especially in commodity exporting countries and commodity related sectors, refinancing pressures may become more acute. This can generate spillovers to the government, as many weaker corporates are state owned. Bank buffers are generally adequate in many emerging markets but may be tested by increasing nonperforming loans (Figure 3). These interlinkages underscore the importance of close monitoring of corporate vulnerabilities, swift and transparent recognition and management of nonperforming assets, and strengthening the resilience of banks.

Among emerging economies, the most important one is China. China continues to navigate a complex transition to a slower and more balanced pace of growth and a more market-based financial system. The Chinese authorities have advanced reforms but the transition remains inherently complex.

Here, the corporate-bank nexus is also critical. Despite progress on economic rebalancing, corporate health in China is declining due to slowing growth and lower profitability. This is reflected in the rising share of debt held by firms that do not earn enough to cover their interest payments. This measure, which we label “debt at risk,” has increased to 14 percent of the debt of listed Chinese companies, more than tripling since 2010.

Increased strains in Chinese firms are important to Chinese banks. This report estimates that corporate bank loans potentially at risk in China amount to almost US$1.3 trillion. These loans could translate into potential bank losses of approximately 7 percent of GDP (Figure 4). This number may seem large but it is manageable, given China’s bank and policy buffers and continued strong growth in the economy. Equally important, the Chinese authorities are aware of these vulnerabilities and are putting in place measures to deal with the over indebted corporates. Yet, the magnitude of these vulnerabilities calls for an ambitious policy agenda: 1) addressing the corporate debt overhang, 2) strengthening banks, and 3) upgrading the supervisory framework to support an increasingly complex financial system.

We need to work collectively to strengthen growth and financial stability beyond the current baseline. This is doable. Policymakers need to deliver a more balanced and potent policy mix that goes beyond continued overreliance on monetary policy. Monetary policy remains crucial but cannot be the only game in town. Well-designed structural reforms and growth-friendly and supportive fiscal policies are essential. In addition, stronger financial policies that further enhance resilience must be put in place. At the global level, the financial regulatory reform agenda must also be completed and implemented—including for nonbanks. All of these actions will help bring balance to the policy mix, and together will make policies more potent and effective.