In the wake of the global financial crisis, monetary and fiscal policies were used aggressively to counteract the effects of the crisis on economic activity. Policymakers look at a number of indicators to guide them in assessing an economy’s level of activity relative to its productive capacity. But trying to figure out the position of the economy in real time is often quite challenging, with consequences for setting policy.

In the case of Brazil in 2011, for example, policymakers estimated in real time that the economy was at a level of output consistent with its productive capacity. Over time, however, the assessment of the cyclical position of the Brazilian economy changed drastically. It had not just been at full capacity, but was overheating. The economy was actually facing inflationary pressures, requiring policy tightening to bring it back to the central bank’s target.

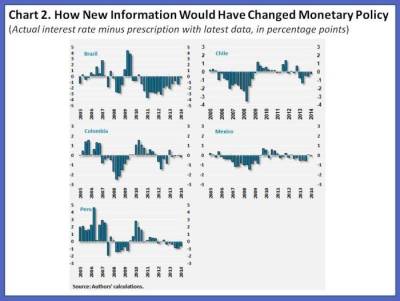

While striking, this experience is not unique to Brazil. In a recent study, we look at the implications for setting monetary policy in real time for a large set of countries, including five Latin American economies (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru).

Output gap: important yet unpredictable

Imagine an economy operating at full productive capacity and a sustainable level of employment consistent with low and stable inflation. In other words, everything is in perfect balance, economically speaking. Economists refer to the amount an economy can produce in this state as potential output. Because it is not directly observable, potential output is difficult to measure. Nevertheless, it is useful to estimate it to serve as a benchmark against the actual state of the economy.

This difference between actual and potential output plays a crucial role in macroeconomics. If actual economic activity is below what the economy can produce at its capacity, stimulative policies (such as lowering interest rates) would normally be put in place to return the economy to potential. Conversely, more restrictive policies would be in order if actual activity is above potential output, to reduce overheating risks that could lead to a sudden, sharp downturn.

A common measure of actual versus potential is the output gap, which is actual gross domestic product relative to its potential level at full productive capacity. Thus, a positive output gap signifies gross domestic product above potential and a negative output gap means there is excess capacity. Economists typically revise their estimates of the output gap to account for new information, so the gap for any given year can change after its initial estimate. This has significant implications for setting policy.

By examining revisions to initial estimates of the output gap, the magnitude of uncertainty surrounding potential output becomes apparent:

- Compared to initial estimates, nearly a third of assessments of output relative to potential reach the opposite conclusion based on subsequent information.

- In real time, economists tend to think slowdowns are temporary in nature, but they are frequently longer-lasting, which only becomes apparent after the fact. Thus, an economy’s potential productive capacity tends to be persistently overestimated.

- Estimates of output gaps are less reliable in recession years, precisely when they are needed the most to enact sound countercyclical policies.

- A low share of the variation in output gap revisions can be predicted ahead of time, making it difficult for policymakers to adjust for this uncertainty when policies are set.

To ease or to tighten, that is the question

Most central banks set monetary policy according to the information they have in that moment regarding the position of the economy with respect to potential output, and the outlook for inflation. When inflation is expected to fall below target, policymakers can lower interest rates to stimulate growth and bring inflation back up; they can prevent overheating and rein in rising inflation expectations by doing the opposite.

Therefore, when formulating monetary policy, it is crucial for central banks to know where economic activity is relative to its potential, especially when operating with a target for inflation. Since Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru have all adopted such targets in the past few decades, we use them as case studies.

- First, we find that if we use revised estimates of the output gap to emulate central banks’ monetary reaction functions, interest rates set by central banks turn out to be substantially different from those that were set in real time.

- Second, we find that these output gap revisions explain almost half of deviations between the actual level of inflation and the central bank’s target. This suggests that output gap revisions bring to light new information that is not accounted for in policy decisions. This occurs, at least in part, because it is difficult to distinguish in real time whether fluctuations in economic activity are cyclical or the start of a change in the trend.

These results underscore the challenges policymakers face when using policy rules that depend on an assessment of the economy’s cyclical position to set the value for interest rates. Policymakers consult a large set of indicators but continue to have difficulties in distinguishing between cyclical fluctuations and shifts in the trend rate of growth. This results in instances where policy would likely have been different if they had known then what we know now.

Looking forward, policy should not be so quick to attribute all movements in economic activity to short-term fluctuations; movements in the trend rate of growth are common and need to be adjusted to more quickly by policymakers. Methods for the real-time assessment of output relative to productive potential also need to be improved. These steps would help illuminate an aspect of making economic policy that is often like trying to find the light switch in a dark room.