A few weeks ago, the Fund suggested that the Federal Reserve could defer its first increase in the policy rate until it sees greater signs of wage or price inflation, with a gradual increase in the federal funds rate thereafter. Such a monetary policy strategy could help avoid the “dark corners” in which, as Olivier Blanchard has argued, small shocks can have potentially large effects. In this blog and accompanying working paper, we expand upon this idea. We also outline the potential benefits of an expanded communications toolkit.

A few weeks ago, the Fund suggested that the Federal Reserve could defer its first increase in the policy rate until it sees greater signs of wage or price inflation, with a gradual increase in the federal funds rate thereafter. Such a monetary policy strategy could help avoid the “dark corners” in which, as Olivier Blanchard has argued, small shocks can have potentially large effects. In this blog and accompanying working paper, we expand upon this idea. We also outline the potential benefits of an expanded communications toolkit.

A gradual pace of policy rate hikes

The United States and the world economy have been preparing for a gradual increase in the U.S. policy interest rates for some time now. The Fed has argued it is likely to start in the second half of this year, but that this will be dependent on the state of the U.S. economy. Indeed, Fed Chair Janet Yellen used the word “gradual” several times in her latest press conference and this message was further underlined by the unhurried pace of policy rate increases forecast by Federal Open Market Committee members.

Preliminary findings of the ongoing IMF health check of the U.S. economy suggest that, despite a weak first quarter, growth in the coming months is likely to pick up, accompanied by steady gains in job creation. In this context, a data-dependent approach clearly calls for a gradual pace of monetary policy normalization. The IMF mission also argued that taking the first step along that gradual path should happen once there are more tangible signs of wage or price inflation than are currently evident.

Balancing multiple risks

The key task of monetary policy today is to weigh the balance of multiple risks. Our paper lays out a framework for thinking about U.S. monetary policy in the face of two-sided but uncertain risks.

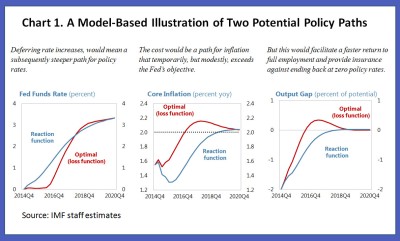

The paper finds that—under conditions of still recovering demand, low inflation, and the policy interest rate near zero—the balance of risks favors more patience to start interest rate increases. The consequence of such a policy would still mean gradual, albeit slightly steeper, path of subsequent rate increases and a modest planned overshooting of inflation.

The intuition is straightforward: it is costly to have the policy interest rate at zero, where the room for maneuver to respond to negative shocks becomes constrained. This is the “dark corner” in the title. Given the potential for future negative shocks that could push the economy back toward low growth and falling inflation, optimal policy should aim to get the economy as quickly as possible back to full employment and away from this dark corner. Waiting a little longer to pull the trigger on policy rates—as former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers says, until the “whites of inflation’s eyes are visible”—provides valuable insurance against ending back at zero interest rates. The case is further strengthened when one takes into account uncertainties related to the amount of slack and the neutral policy rate.

Such a policy has the potential to temporarily generate a bit more inflation (see chart). But that’s okay and, we think, a reasonable cost to pay. After all, expectations are well anchored and the Fed has strong credibility and a proven track record in addressing inflation, when it arises.

Effective communications can be a powerful monetary policy tool

We also argue that there are steps to further strengthen the effectiveness of the Fed’s communication strategy that could help avoid the dark corners. As Chair Yellen said in a 2013 speech, the effects of monetary policy depend critically on the public getting the message about what the Fed is expected to do in setting the policy interest rate months or years in the future.

Flexible inflation targeting, as now practiced by a number of central banks, provides a useful template for this purpose. While the specific structure of these regimes has differed across countries, the adoption of numerical inflation objectives has strengthened the emphasis on the communication practices of central banks.

There is room to further improve the Fed’s communications framework. To better guide expectations and provide clarity to markets about the Fed’s inflation and output objectives and intentions, the Fed could start publishing a regular monetary policy report that contains forecasts for key economic indicators—inflation, output, and interest rates—as well as alternative scenarios to illustrate how it sees the uncertainties around that outlook. A report with consistent macroeconomic forecasts could be a tremendously valuable communication tool. For example, in the current situation, it could provide a clearer picture of the “gradual” path Chair Yellen has emphasized in her policy communications, focusing attention on the whole road ahead while diluting attention on the specific date of the initial policy interest rate increase. After all, it is the full path of rate increases that really matters for the economic outlook.

There are certainly logistical challenges in implementing such an approach, not least in forging an agreement on a path for policy rates within a large and diverse Federal Open Market Committee. However, these should be outweighed by the exceptional value of a fully articulated and internally consistent forecast, published in a regular monetary policy report and endorsed by the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee.