(Version in Español)

Something unusual happened this year. For the first time in almost ten years, a book by an economist made it to Amazon’s Top 10 list. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century captured the attention of people from all walks of life because it echoed what an increasing number of Americans have been feeling: the rich keep getting richer and poverty in America is a mainstream problem.

The numbers illustrate the troubling reality. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 1 in 6 Americans—almost 50 million people—are living in poverty. Recent research documents that nearly 40 percent of American adults will spend at least one year in poverty by the time they reach 60. During 1968–2000, the risk was less than 20 percent. More devastatingly, 1 in 5 children currently live in poverty and, during their childhood, roughly 1 in 3 Americans will spend at least one year living below the poverty line.

Also worrisome is that the poverty rate increased sharply during the recession and has not come down. The rate still hovers above 15 percent despite the ongoing recovery (see Chart 1).

Unless the economic benefits of an improving economy are felt more widely, this recovery may well prove neither economically nor socially sustainable. The United States needs more jobs that pay decent wages. In our recent report on the U.S. economy, we argue that extending certain tax credits, together with increasing the minimum wage, are effective and efficient ways to help the working poor.

Statistics with consequences

Poverty has a self-sustaining nature. People who have been sucked into poverty in the past are more likely to fall back below the poverty line in the future. And, the longer they spend below the poverty line, the harder it is to exit.

Poverty also becomes ingrained across generations. Children growing up in poverty often lack the advantages of sufficient nutrition and a stable home. They underperform in school, have limited access to quality health care or education, are less likely to go to college, and find themselves less prepared to compete for the high-skilled jobs that the modern U.S. economy demands.

This becomes a vicious cycle that leaves the poor lacking the resources or opportunities to exit. Stuck in low-paying jobs and faced with economic insecurity, the poor become more likely to get detached from the labor market and less likely to make investments in education and job training—which could help them break the cycle.

At a macroeconomic level, both labor force participation and productivity suffer as a consequence. Poverty reduction is therefore important for long-term growth, and is essential for both economic and social sustainability in the United States.

Supporting the poor

A good chunk of the poor are unfortunately among the ranks of the unemployed. To lift them above the poverty line will require, at a minimum, greater job creation and stronger economic growth.

But this is not enough. There are 10.6 million poor people who have a job, and often head households with children. Modest policy efforts can help change the negative dynamics that poverty creates. Luckily, there are tools that can help and which have a proven track record.

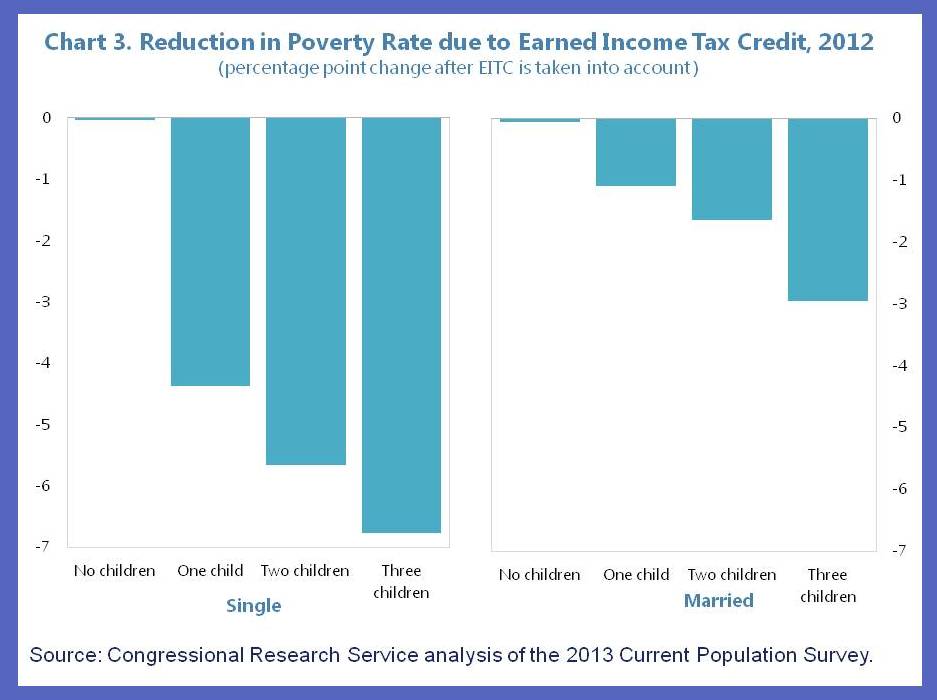

In particular, the earned income tax credit program is a well-targeted mechanism to address poverty by offering tax refunds to those workers that earn below certain income levels. Eighty percent of the tax credit resources accrue to those in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution. This tax credit, together with the child tax credit, helps reduce poverty rates among the nonelderly more than any other program (see Chart 2). Expanding the tax credit, especially to those without children, would help lift more workers out of poverty (see Chart 3). And the fiscal costs are very manageable—we estimate less than 0.1 percent of GDP per year.

An increase in the minimum wage would complement the expansion in the earned income tax credit. One negative side effect of a more generous tax credit is that it has the potential to lower pre-tax wages of low-income workers, causing workers to see a reduction in their take-home pay (a more generous tax credit would entice more people to enter the labor force, increasing the supply of labor and pushing wages down). To short-circuit this effect, a higher minimum wage could effectively limit the degree to which the tax credit is able to drive down pre-tax wages. It would also shift some of the fiscal costs of a broader tax credit onto companies (rather than being paid for by the budget).

Today, a single parent working full time at the federal minimum wage rate earns $15,080 a year, a level that is well below the official poverty line of $16,057. Moving the minimum wage up somewhat from its current level seems justified. While there is a chance that a higher minimum wage would discourage some employers from hiring low-wage workers, research shows a relatively small effect on employment.

Time for action

The belief that anyone can make it if they get a good education and work hard has been a cornerstone of the American identity. By helping poor families make ends meet, a combined expansion of the earned income tax credit and a modest increase in the minimum wage would bring the United States a step closer to realizing that aspiration.