A leading progressive economist proposes steps to transform the US economy at this critical juncture

The COVID-19 pandemic is shining an unforgiving spotlight on the many inequalities in the United States, demonstrating how pervasive they are and that they put the nation at risk for other systemic shocks. To stop the spread of the virus and emerge from a crushing recession, these fundamental inequalities must be addressed. Otherwise not only is a slow economic recovery more than likely, but the odds grow that the next shock—health or otherwise—will again throw millions out of work and subject their families to fear, hunger, and lasting economic scars.

Before the pandemic, the United States was in the midst of a decade-long recovery from the Great Recession, which began in December 2007. But not all Americans experienced that recovery in the same way. The top 1 percent emerged as strong as ever in terms of wealth, regaining what they had lost by 2012. As of March 2020, however, US working- and middle-class families had barely recovered their lost wealth, and many families, especially those of color, never recovered. Even amid a strong recovery, the United States was burdened by extraordinary economic and racial inequality.

Today, stark differences among US workers and their families make the current recovery neither U- nor V-shaped but rather one that resembles a sideways Y, with those benefiting from a stock market recovery or employed standing on the branch of the Y that points up unaffected by the recession, and those on the bottom branch facing perhaps years of struggle. And there are stark differences of race and class between the upper and lower legs of that sideways Y. This recession provides an opportunity for policymakers to address these inequalities with transformative policy changes to produce a healthier and more resilient economy that delivers strong, stable, and broad-based growth and prosperity.

Disparities abound

Workers and their families on the wrong side of the many US economic disparities are there for several reasons—including a stubborn reliance by policymakers on markets to do the work of government and the racism and sexism, sometimes written into law, that blind policymakers to injustice and to economic sense.

This article will identify specific causes of economic inequality in the United States and then explain how to address them.

Markets: Beginning in the 1980s, conservative economists began to make the case that unfettered markets were the only way to deliver sustained growth and well-being. This ideology, with modest exceptions, has governed US economic policymaking ever since. But it has not delivered. Moreover, the supposedly neutral and fair rules that govern markets have in fact shifted economic risk away from corporations and the wealthy toward medium- and low-income families. This has never been more apparent than now, when the coronavirus has caused mostly low-income workers to either lose their jobs or have to work in employment that exposes them to the risk of contracting and spreading the disease.

Tax cuts, weak public investment: President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cut, which benefited largely the better-off, is only the most recent manifestation of a tax-cutting philosophy that has governed US fiscal policy for decades. These measures have starved the nation of resources that could be used to fund basic governmental functions and critical public investments. As a result, public investment as a share of GDP—the value of goods and services produced in the United States in a year—has fallen to its lowest level since 1947.

Loading component...

Eroding worker power: The ability of US workers to bargain for higher wages and benefits and better and safer working conditions has been sapped by years of anti-union court and administrative rulings. And in 27 states, right-to-work laws make it harder for unions to form. As employers gained the upper hand, wages stagnated, and worker safety has suffered, especially during the pandemic.

Economic concentration: US antitrust policy and enforcement have allowed industries across the United States to become increasingly concentrated, giving large businesses market power to set prices, eliminate competitors, suppress wages, and hobble innovation. What’s more, there is evidence that this is dampening firms’ investment. Some are thriving in the midst of—indeed because of—the pandemic, while small businesses struggle to survive.

Measuring the economy: Before the 1980s, when US economic inequality began its upward trajectory, growth in GDP was a reasonably reliable indicator of the well-being of most Americans. But as economic inequality has risen close to its 1920 levels, the benefits of GDP growth have gone disproportionately to the top 10 percent of earners, while income growth for the vast majority of people has been slower than that of GDP—in some cases, none at all. For that reason, GDP reflects mostly how the better-off are doing. As GDP recovers in the coming months, therefore, it will give policymakers false signals about whether average Americans are recovering.

Racism and sexism: The disparate health and economic consequences of the coronavirus recession reinforce the reality and history of racism and sexism in the United States. The median earnings for a Black household are 59 percent of those of a White household, and for men and women of all races, a median woman earns 81 cents for every dollar earned by a man. The results of job segregation are apparent, with health care and service workers on the pandemic front lines. Despite being essential, some of these jobs—in which women and minorities are overrepresented—are the least likely to have benefits such as paid sick time or employer-provided health insurance.

These problems are largely the result of decades of failed policies supported more by ideology than evidence. A distorted economic narrative that lionizes markets has led to the weakening of public institutions and the acceptability of less funding for democratic institutions of governance, greater economic concentration, reduced worker power, and the discriminatory effect of laissez-faire labor rules. The role of policy choices in arranging the market structure is unmistakable and enduring.

Building a strong, equitable economy

Transforming the US economy requires policymakers to recognize that markets cannot perform the work of government.

The first step is to eradicate COVID-19. It has to be the first priority, not only for public health but also for the US economy. Beyond that, encouraging a strong and sustained recovery that delivers broadly shared growth also requires the United States to address its long-term problems: a costly health system that leaves millions with insufficient care, an education system designed not to end inequality but to preserve it, lack of basic economic stability for most families, and climate change.

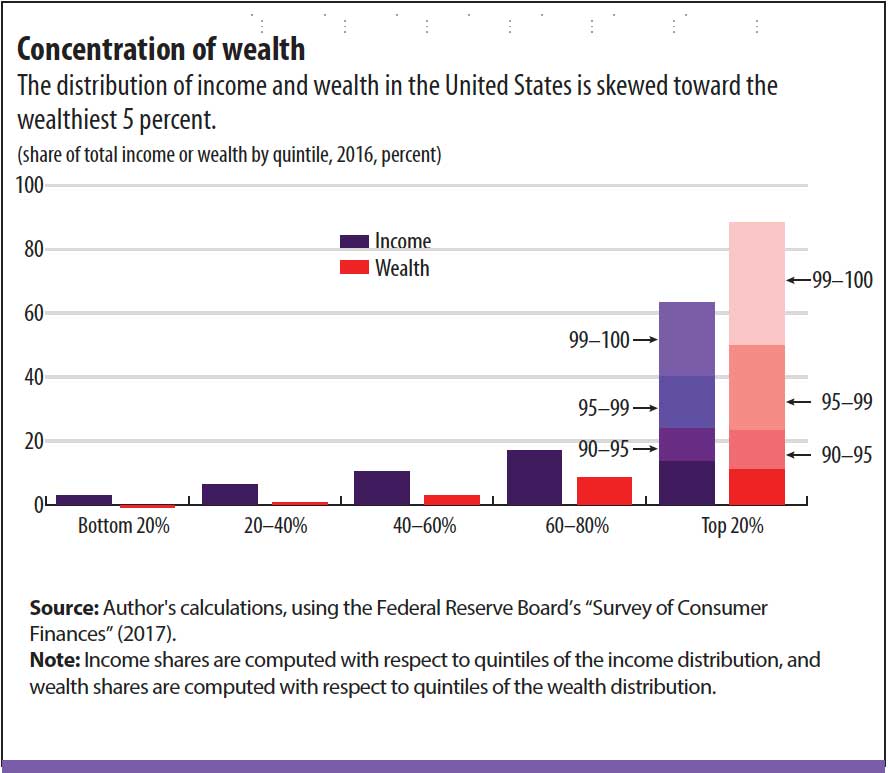

Major public investments are required to deal with each issue. While it is not necessary to worry now about paying for them, the nation should put in place significant tax increases, primarily or entirely on the wealthy, to begin investing in these long-term solutions. The country should tax the enormous wealth concentrated at the top that is being saved, or kept overseas, and not being invested in the economy or in solving societal problems (see chart).

Policymakers also must address the economic concentration that has created monopsony power (a single or handful of buyers or employers) that keeps wages down and threatens small businesses, which are the lifeblood of innovation and economic dynamism. The first step is to ensure that the recession and the programs designed to help businesses survive the crisis don’t exacerbate this trend. Thus far, federal policies to address the economic downturn have provided far greater aid to large businesses than to small ones.

Policymakers also must ensure that federal government funds are directed to productive uses that support workers and customers, and not to rewarding wealthy shareholders. Corporations receiving aid should be barred from issuing dividends and carrying out stock buybacks, and banks should be required to suspend capital distributions during the crisis to support lending to the real economy.

Even more fundamental to addressing excessive concentration is strengthening US antitrust enforcement, which is weaker than it has been in decades. The antitrust laws themselves also need to be bolstered, particularly with respect to the rules governing mergers and exclusionary conduct. Legislators should consider creating a digital regulatory authority to enforce privacy laws and enhance competition in digital markets.

The country also needs to better understand who benefits, or does not, from recovery policies and what further actions are needed. Because overall GDP is not up to that task, income must be disaggregated at all levels to measure progress or lack thereof for all groups—which would enable the United States to lay the groundwork for understanding what other actions are needed to ensure more people benefit from the recovery.

US economic inequality is firmly tied to the issue of racial inequality. The unmistakable message of the Black Lives Matter movement is that Americans of color never have been able to trust government to act on their behalf. Government must work to ensure that low-income Black, Latinx, and Native American people can both develop and deploy their talents and skills in the economy.

Taxing wealth, which is disproportionately owned by White Americans, is one solution. But for that to address racial inequities adequately, the proceeds of the wealth tax must benefit the majority of the nonwealthy. The proceeds must be directed to the most urgently needed investments, such as in COVID-19 testing and treatment in communities of color, in policies that expressly and progressively support low-wage workers and care workers, and in engagement with minority-owned small businesses. Otherwise, pervasive inequities will be further entrenched.

A significant reason for the gender earnings gap is the lack of a national paid family and medical leave policy and the absence of a national program to ensure that families have access to quality, affordable "> childcare and prekindergarten education. Families with children that do not have access to paid leave and childcare—or cannot afford them—have little choice but to put careers on hold. This happens to women far more often than to men. Legislation has been introduced in Congress to accomplish both of these goals, and these measures should get serious consideration in the next Congress.

Reason for optimism

There is reason to believe that the United States can enact policies to transform its economy and society. Until recently, some of the conversations taking place among policymakers and around dinner tables—inspired by COVID-19, the deep recession, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the recent presidential election—would have been relegated to the edges of public debate. Today that is not the case.

Yet the US political system is beset by deep partisanship and a constitutional and electoral system that makes it far easier to block transformative policies than enact them. But I am an optimist, and I still believe that the country could be at an inflection point, with the advantage going to those who develop and advocate progressive policies to reduce inequality and build an economy that produces strong, stable, and broad-based growth.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.